6/18/09 Peru

The Beginning:

(a summary of john quillen and brian moran's ascent of pisco and huascaran)

It was an opportunity of

a lifetime. Travel to Peru and climb some tall peaks. Indeed, the

Cordillera Blanca is like the mini Himalaya. Climbers from all over the

world converge on this place to rope up and tackle any number of various peaks

from simple high altitude walk ups to serious big wall ice climbs. As for

us, our goal was simple. Undergo an acclimatization program ultimately

ending on Huascaran Sur, the highest peak in Peru and fifth highest in South

America. When we landed in Lima, we would board our bus to Huaraz the

following morning. This meant a fitful night of sleep on the floor of the

airport. Our bus ride was eight hours and it was the most nauseating ride

in the world. Four hours of it were through curves that resembled the

dragon on 129.

We arrived in Huaraz and

were escorted to our hotel. The staff was very friendly, money goes a long

way in South America. For 40 bucks a night, we had primo accommodations,

probably the second nicest place in town. The owner, a Norwegian, made

friends with us and invited us on an acclimatization hike up to lake Chirrup the

following day. It was an offer to good to refuse as we had considered this

as a great warm up to Pisco anyway. Lake Chirrup and Mt. Chirrup are in

the 14k to 16k foot range. It took us a few hours to gain the lake

and it was a beautiful sight in the shadow of Mt. Chirrup. I seemed to do

real well with the altitude, Brian chewed his coca leaves for acclimatization.

In fact, we were served coca tea immediately upon arrival in Huaraz.

Another interesting side note is that we went to the pharmacy to secure

emergency high altitude medications. We were immediately handed zanax.

You can secure most anything in Peru, for a price. We skipped on the

zanax.

Getting to Chirrup

involved a 1.5 hour bus ride that the owner had chartered from the hotel for his

friends from Lima.  They were in marginal

shape and we spent a lot of time waiting on them at the bus, three hours to be

exact. I don't think they had much business at that altitude in that kind

of shape and didn't seem real apologetic for making everyone wait either.

Nonetheless, we were very happy with the trial run and our bodies ability to

handle the heights.

They were in marginal

shape and we spent a lot of time waiting on them at the bus, three hours to be

exact. I don't think they had much business at that altitude in that kind

of shape and didn't seem real apologetic for making everyone wait either.

Nonetheless, we were very happy with the trial run and our bodies ability to

handle the heights.

The next day we planned

to secure a cab over to Yuangay and proceed over to Cebollopampa and begin our

ascent of Pisco. At 19000 feet, Pisco is an often climbed mountain with

some real alpine glacier travel and crevasse negotiating. The thing about

Peru is you can never trust anyone's word or a bit of info on Summit Post.

From the beginning on Pisco, our packs were every bit of 75 lbs. Brian and

I were prepared to carry it all ourselves to the moraine camp. Early that

morning, I became somewhat stomach sick and the three hour dirt road cab ride

didn't help things very much. I dosed up on medicine and made it to

Cebollopampa  where

fortunately, the mules were waiting to haul our equipment to the moraine camp.

I was elated. Yes, it felt like cheating but my stomach was acting up it

and seemed a Godsend.

where

fortunately, the mules were waiting to haul our equipment to the moraine camp.

I was elated. Yes, it felt like cheating but my stomach was acting up it

and seemed a Godsend.

Summit Post told

me that it was a 2 hour walk up to the Refugio at Pisco. What ensued was

the most hellish hike of my life. As you can imagine, the medicine had

worn off and the illness was now in full swing. Without going into too

much detail, I will suffice it to say that I could take no more than 20 steps

before having to accommodate the expulsion of fluids from my body. Which

end depended on the vagaries of the "Duchess", a.k.a. my stomach. I have

taken to naming her that because she is such a precarious, fickle and attention

seeking little royal pain that rears her head anytime I am in dire straits and

need for her to behave. All my travels to a foreign country of less

hygienic repute have been impacted by the Duchess' royal temperament. This

situation was no different. Why could this not have waited until I gained

the Refugio? By now, Brian and the Burros were gone, along with all my

gear, water, jacket and medicines. 20 steps, stop, expel fluids, march on.

Praying for the strength to make the Refugio, I had no choice. Retreat was

not an option. Brian had moved on. All I wished for now was water.

I was parched. I had 3000 feet to climb. What Hell this was going to

be. At one point, I stopped to have another episode and a descending group

of climbers gave me wide berth. I recognized the face of one of them, it

was the guy we spoke with in town at one of the outfitters shops. He

looked at me in horror. Another Italian patted me on the back and told me

to descend, that I was altitude sick. I explained that it was not

altitude, I had a stomach bug and he marched on. I appreciated his

gesture. I have been in situations resembling this before. I have

learned to practice every precaution in my travels to avoid such incidents.

I had the right medicines, vaccinations and ate no questionable foods. In

Ecuador, I made the mistake of putting my toothbrush into the tap water.

That's all it took. No such deal here. All bottled water, the best

restaurants in town, everything. How did this get me and not Brian?

That little princess went out of her way to find the bad stuff on this trip.

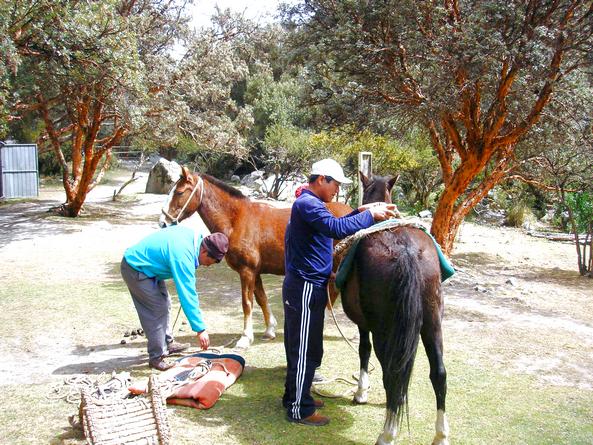

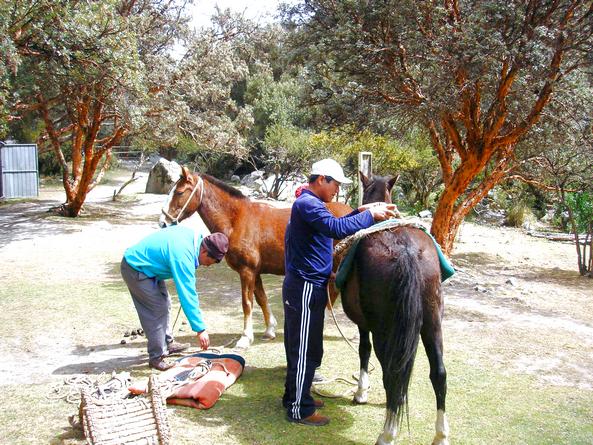

Several hours into the death march came a reprieve. That guy pictured

above was descending. I was sitting on a rock heaving my guts out and he

wheeled the burro around for me to mount. It could have been a cat and I

would have boarded. There's an old saying in N.A and A. A. You can't

save your face and your ass at the same time. I was glad that the ass

saved my face on this one. As I rode him the last mile to the Refugio, I

literally fell off him onto the ground. It was a rough ride, considering

all the factors. (burros that did

double duty for JQ)

(burros that did

double duty for JQ)

When I fell off the

burro, I stumbled into the Refugio in search of my backpack. I immediately

pulled out my down clothing and set to work crawling inside of it. The

fever was on and I was trembling with the cold. I stumbled into the

kitchen area and pulled the hood over my head. I was in another world at

15000 feet. Survival was my only goal. Someone helped me to the bunk

upstairs and put me in my sleeping bag with a hot water bottle and a bucket next

to my sleeping bag. For the next 12 hours I was in a daze of

hallucinogenic fog. At one point, Brian felt my head and proclaimed that I

was hotter than a stove although I was ensconced in the down clothing and down

sleeping bag. I don't remember much over the next day or two, finally

waking up long enough to go to the bathroom. I drank some water.

Life returned to my body again and I became very warm now. The fever had

broken, I might live. By now, Brian was summit focused and forced food on

my to get my mind headed in that direction. I told him there was no way I

was going for the summit now. I understood his frustration but I was sick.

He was pushing me to get well and that just wasn't going to happen because he

was in a hurry for the summit. We waited another day and I began to eat

and drink. Another day made the world of difference in addition to the

cipro dosages. Yes, I might live. Climbing was another story.

We would work on the ascent of Pisco in the morning.

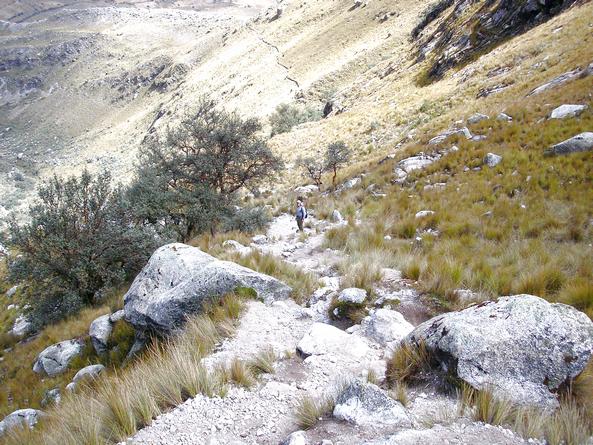

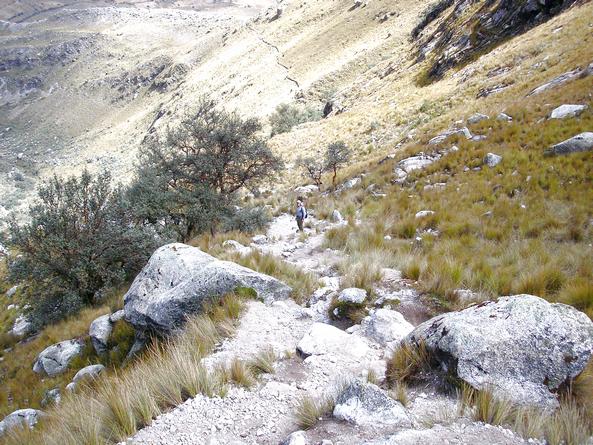

During my illness, the

impatient brian had scouted a route through the moraine to the summit, or so I

thought. As you can see, the moraine is a real pain in the butt.

Several hours of scrambling in the dark and light for a trail so faint you

couldn't see it unless you have hiked it.

(this is a pic of the part of the

moraine trail, can you imagine finding it in the dark? It proceeds out of

the pic on the left, over that big hill to the Refugio for miles)

(this is a pic of the part of the

moraine trail, can you imagine finding it in the dark? It proceeds out of

the pic on the left, over that big hill to the Refugio for miles)

Through no fault of

Brian's, we got lost on our alpine start. I certainly had no inclination

of the trail direction. My only focus for those days was not dying.

We stumbled around in a snow storm trying to crawl over icy rocks and possibly

see a trail. This was a true exercise in

futility. When I continue, I will share

the story of our time on the glacier and near Pisco's summit flanks. Stay

posted, it is worth reading.

Part 2: The Pisco Attempt:

We decided to embark at 1 am

and that was a wise decision given the difficulties were were destined to

encounter. Losing the ability to follow any headlamps through the moraine

field briefly characterized above, we scrambled until hopelessly lost at 3 am.

When we started, the snow was light, by the time we crested the hill, the snow

was sticking to any surface making our rock hopping even more interesting.

We would follow a trail only to see it peter out, retrack to the point of

departure and head another way. I realized the futility of this course and

suggested we wait until headlamps appeared. The folks behind us had the

good sense not to follow our stupid souls and I convinced Brian of the notion of

following them. Sometimes pride is a strong thing but he eventually

relented and we were no on the crest of the moraine, hopefully headed for the

glacier at a somewhat late hour of 5.30 am, four and a half hours after

departing from the refugio at 15,500 feet. Things were now in line.

We were headed up to the glacier.

The sun crested the summit

of Pisco and lifted our spirits. Unfolding before us was the lip of the

glacier with (beginning of

glacier)

(beginning of

glacier)

several footpaths

crossing a few smaller crevasses. We took some time roping up and doing

security checks and it was off to the races. I noticed that the altitude

was definitely taking some effect upon me as my breathing was very labored.

I was gasping for air. (I now realize it was a cumulative effect of

dehydration and just being weakened from the illness the days before our summit

attempt.) Brian would take a few steps and pull the rope, I would lean

over my ice axe and gasp like my head had been underwater. Either way, we

were making progress up the glacier. Each new hill presented another new

snow hill. The hill climbing was endless. If you have ever wondered

why you don't get to see the steep stuff in climbing videos, this is the reason.

While exerting like that, the last thing on your mind is any extraneous

videography. Breathing is critical. It must have been about 8 am

when we got to the end of the foottracks. We knew that several teams were

above us and indeed the summit was in sight. We began to question our

choice of routing. Were these old tracks? Had we somehow missed a

turn in the low light and been following an old route? We proceeded

onward. It certainly had to be a matter of distance and they had been

moving quite rapidly, those danged Germans.

We would crest a steep snow

slope only to be presented with another steep snow slope. As I peered over

towards the summit, I noticed we were going around the horn, so to speak and

coming up the rear flank of the mountain. That is always the way things go

in the mountains, large or small. You can look at the summit and assume

that the route will follow the most circular and lenghty clip to the top.

It looked like I could throw a rock and hit the top. We stopped again.

Now we were making our own tracks. In retrospect, the previous

footracks had just been covered by the windblown snow. We stopped for a

break. I remember cursing. Then we were enveloped. Not just

kind of covered in a cloud, but totally enveloped in white. I could not

see Brian on the rope ahead of me. It was a total whiteout. Time now

was about 9 am. Our decision was made. Brian mentioned

something about a turn around time. I told him, this is it. He knew

what we had to do. Descend.

(whiteout on Pisco)

(whiteout on Pisco)

Getting down from mountains

is usually a very simple chore. The amount of energy required versus the

alternative is minimal and each descending step ensures restored vitality to

lungs, legs and heart. I can literally, skip down a mountain.

However, the Germans still managed to pass us. Those long legged,

genetically superior alpinists. Or should I say, Andinists. Yes,

that is a new word that entered my lexicon in Peru. Apparently, if you

climb down there you are not an alpinist but an andinist. Rock on

andinistas. They let us know that we were very close to the summit but it

was a "son of a bitch" in their broken english cresting the lip of the top as

there was a nice little crevasse to gain before the "cumbre". I know they

were in their twenties but it seemed like second nature to them.

(the top we never made)

(the top we never made)

When we returned to the lip

where the glacier meets moraine, we took a long break and stared back at the

summit which was now clear and unfolding in all her glory to spite us.

Someone said a discouraging word and someone made a vulgar gesture in her

general direction. Pisco my rear. You haven't heard the last from

us. Brian and I had significant difficulty securing our gear and moving

down the moraine. We were beat. It was now probably 11 am, ten hours

after departure. We had to force ourselves to move down the hill.

The sun beat down and it got really hot. We were out of water. i

have never remembered such a brutal rock walk in my life. We were wearing

double plastic boots and the scree would blow out every four steps and make you

lose your footing. I hyperextended my knee at one point.

Dont know if I mentioned the

narrow ledge upon which we had to ascend and descend the moraine but if you

fall, here is a snapshot of what that could resemble.

(I took this directly

from the trail. Sometimes it is beneficial NOT to see what you are

climbing in the dark)

(I took this directly

from the trail. Sometimes it is beneficial NOT to see what you are

climbing in the dark)

As we stumbled down the

moraine in the blaring morning sun we passed a large expedition with porters

ferrying their loads to the toe of the glacier. Smart idea. I would

tuck that away for future use. Had we done that, several hours would

have been shaved from our time making the summit a cinch. Hindsight, this

is a learning experience.

By 2 pm, we had almost

finished the moraine ordeal. I could see the lip of the last big 200 foot

hill of scree to top and drop back down to the refugio. There was a group

of young people standing and peering down at me. I must have looked a

sight. Mustering all the strength and sipping my last bit of water, I

began the slip trail up the talus slope in the blistering afternoon sun at 16000

feet. When I finally made the top, the crew looked at me as if I had

emerged from that lagoon. Their affect noticeably changed and their

previously jovial mood turned more somber as they considered the toll this climb

might take upon them, should they decide to continue to following day. I

dropped down to the refugio where Brain met me and offered to take my pack.

I declined and ambled over to the refugio where he had ordered me the best coca

cola I ever had. We took just enough time to pack up and make the final 2

hour push to Cebollopampa and catch a taxi back to Huaraz. It's amazing

how refreshed I felt after changing out of the boots, placing my gear upon the

burro and walking down the last 3000 feet to the staging area for Pisco. I

passed all the places upon which I had deposited bodily fluids several days

before and relished the rejuvinated body that allowed me to descend under my own

power. Who cares if we didn't summit. I was done with mountaineering

for good. When we arrived at Cebollopampa there was a problem. No

cab to Huaraz. Three hours is a long cab ride, not to mention hike or

hitch. We begged, bartered and pled with a local jewish group to let us

tag onto their bus. Their driver relented and we were off to Huaraz.

By 9 pm we arrived in the city to the delight of our hotel Gerente, Pascal.

He was prepared to send the Alpine Rescue association to fetch us. He

said, "Pisco is a 3-4 day climb, you were gone 5 days, what

happened?"

Next installment:

The Huascaran Experiment. (now

live, click title)

They were in marginal

shape and we spent a lot of time waiting on them at the bus, three hours to be

exact. I don't think they had much business at that altitude in that kind

of shape and didn't seem real apologetic for making everyone wait either.

Nonetheless, we were very happy with the trial run and our bodies ability to

handle the heights.

They were in marginal

shape and we spent a lot of time waiting on them at the bus, three hours to be

exact. I don't think they had much business at that altitude in that kind

of shape and didn't seem real apologetic for making everyone wait either.

Nonetheless, we were very happy with the trial run and our bodies ability to

handle the heights.

where

fortunately, the mules were waiting to haul our equipment to the moraine camp.

I was elated. Yes, it felt like cheating but my stomach was acting up it

and seemed a Godsend.

where

fortunately, the mules were waiting to haul our equipment to the moraine camp.

I was elated. Yes, it felt like cheating but my stomach was acting up it

and seemed a Godsend. (burros that did

double duty for JQ)

(burros that did

double duty for JQ) (this is a pic of the part of the

moraine trail, can you imagine finding it in the dark? It proceeds out of

the pic on the left, over that big hill to the Refugio for miles)

(this is a pic of the part of the

moraine trail, can you imagine finding it in the dark? It proceeds out of

the pic on the left, over that big hill to the Refugio for miles) (beginning of

glacier)

(beginning of

glacier)

(whiteout on Pisco)

(whiteout on Pisco) (the top we never made)

(the top we never made) (I took this directly

from the trail. Sometimes it is beneficial NOT to see what you are

climbing in the dark)

(I took this directly

from the trail. Sometimes it is beneficial NOT to see what you are

climbing in the dark)