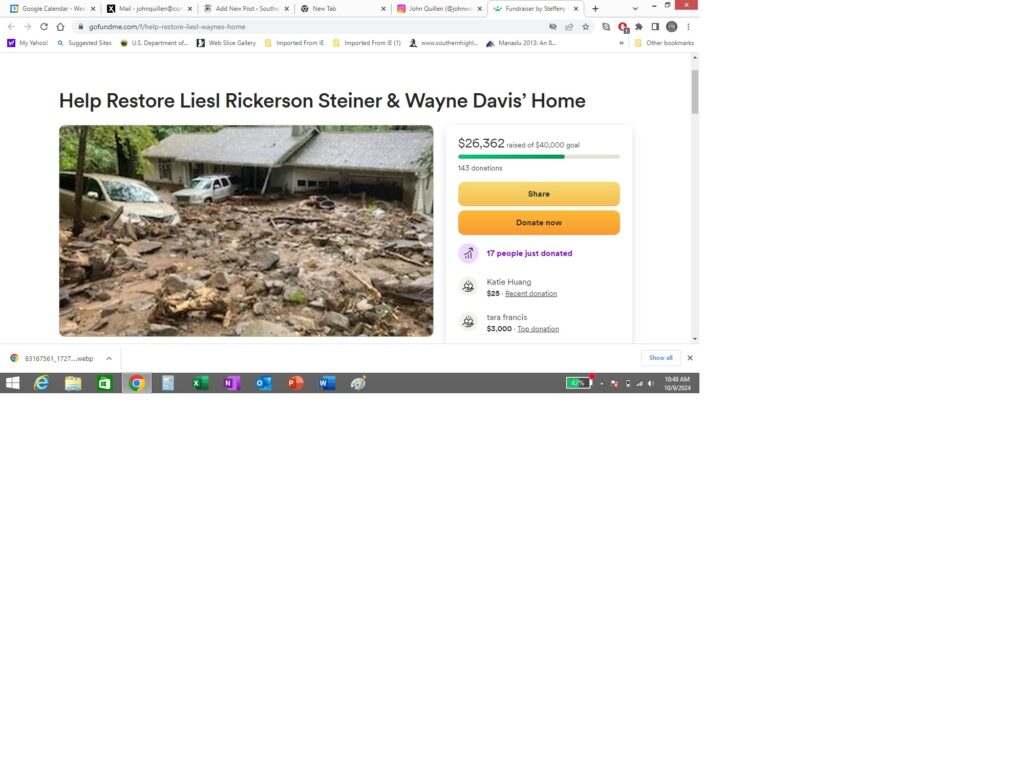

Help Wayne and Liesl

Last weekend I went to North Carolina to try and assist with the hurricane relief effort. Due to some misinformation we were not needed over there. Someone had posted on facebook they needed people to backpack in supplies, which may have been the case early on but was definitely not when we arrived. In fact, we went to three separate distribution centers as deep as you could go in the Carolina mountains before the road petered out entirely. It was like a forward firebase in Vietnam with all the helicopter traffic, ATVs and supplies in there.

If you read my last column on the firetowers then you will notice the name Wayne Davis. He lost his life’s possessions in this flood.

If you really want to help someone, then consider my friend Wayne and his partner who lost their life in this catastrophe. Here is a link to their gofundme. I can verify this is legit and the money will go to them and not some random agency. I can’t get to him still so let’s just give them the means to obtain what they need. Here is a link to the donation page for them.

The Firetowers

Recently published column in Cityview Magazine https://cityviewmag.com/our-history-with-a-view/

Time is running out to experience the fire towers of the Smokies

There used to be 17 fire towers in the Great Smoky Mountain National Park that were utilized prior to the 1930s by the Forest Service. I know little of their effectiveness in those days or what someone was supposed to do when they saw distant smoke prior to air drops from big planes. But I would have stood in line for that interview to get paid to sit on top of a mountain and have my coffee with the day breaking over the oldest mountains in the world.

One of my favorite bushwhacks runs up Groundhog Creek on the park’s western end. Many cool mornings have found me crawling through snow, getting smacked by rhododendron while scrambling Class 3 rock. Rising over 2600 feet from its start in Cosby, this path bounds and weaves through the stream until crossing the Lower Mt. Cammerer trail well past a backcountry campsite. I know better than to tread here in warm months as clawing loose ground is preferable to a tail full of rattles on these now rocky, precipitous slopes.

On one visit in particular, my objective comes into full view as sunlight bounces from its chipped windows: The Mt. Cammerer Fire Tower. An hour or so in to our trek and the crawling is about to commence. I’ve made this journey a dozen times but distinctly recall how this notion first came about. Wayne Davis told me he thought we could skinny up from his cabin at the park boundary.

I thanked him for volunteering to lead me as he reluctantly signed on for the initial part on a cold, January morning. His look when I shoved micro spikes and mountain gear in the pack prompted, “..but only to the lower trail,” from my friend. Wayne had plenty of opportunities to turn around and retreat to the warmth of his wood stove so he can’t blame me for what happened next.

Due to some navigational “challenges,” I will call them, we clawed to the foot of this defunct structure as the sun was dipping low on the North Carolina/Tennessee border we were straddling. Mt. Cammerer saw us emerge from the foliage drenched in sweat and clothed in dirt. Snagging sunset shots from this fire tower wasn’t necessarily the plan but we nailed some spectacular vistas as the temperature followed the waning sun. Alone in this room with a view, darkness now crept up the valley to our 5000-foot elevation. Although remodeled in the ’90s, Mt. Cammerer Fire Tower was missing windows and groaned all winter night.

You see, Wayne didn’t have all the down garb as he had only intended to join me for a small, initial portion of this ascent up the creek. I seem to remember him toting a coffee mug clad in sneakers. But these adventures and some friendly goading can lure you skyward bearing out Cammerer’s reputation as a siren of the Smokies. There’s an old mountaineering adage which implies that the word bivouac is French for “mistake.” A bivouac was in order here as we considered the icy descent and inherent dangers therein. A less than restful night atop this iconic peak ensued as we channeled the spirit of caretakers long past. I had enough extra snacks and clothing. The floors squeaked and windows rattled with the constant winter breeze. Like the old caretakers, we scanned the ridges leading up to our spot and swore we saw bobbing headlamps all night long.

First light was a welcomed sight as we rose from where we leaned against the inner frame of this octagonal structure. Its stone and wood facade were wrapped by a 360-degree porch, perfect for chasing the views in all its elusive, cloud-filled glory. Rays pierced a blanket of billowy cotton draping the valley from which we rose the day before. White Rocks is what the Native Americans called this place. To Wayne and me, our night atop Cammerer will forever remain an indelible mountaintop experience.

I have a similar relationship to the Shuckstack Fire Tower on the North Carolina side of the Smokies. On our annual canoe pilgrimage over to Eagle Creek, the day hike up one of the park’s steepest trails, Lost Cove, tops the agenda. Despite some mild protestation from my friends, the climb to the Appalachian Trail and eventual spur off to the metal structure is its own breathtaking reward. From this vantage is seen three states and peaks from the Blue Ridge down into Georgia across beautiful Fontana Lake. I don’t expect them to allow us up there for long given the declining health of this metal perch. Holes in a plywood floor and rattling handrails give pause to many who claim the base as their summit. But then they’d miss one of the best views in the Southeast.

The last remaining tribute to a century-old fire mitigation method, Mt. Sterling tower is an exact duplicate of the Shuckstack in identical disrepair. The views up there are much scarcer as that side of the park experiences continuous clouds moving in from the west. If you time your hike accordingly to catch a break, however, you soon realize that blip directly across from you is Cammerer, although many trail miles and climbs separate these Smokies sisters. Movements to restore these towers have fizzled like distant smoke so I would simply suggest you get up there and visit these survivors before they melt into the mist with the ghosts of their caretakers and furtive glimpses they afford.

the West Highland Way.

this hike has been on my mind for a little while. And like most of my adventures that happened fortuitously with a drop in airfare from New York to Edinburgh Scotland. How can I pass up $500 round trip? So I started cramming my online research.

We started off in Edinburgh. From there it was a train ride to Milngavie. Traveling is so simple in Scotland they have a wonderful rail service.

And almost as if on cue, the rains began as we embarked. We had 96 miles in front of us.

the trail passes right by the Glencoe distillery. So we made a side trip.

we had planned to hike into Drymmen for our first night. But pushed on when we heard there was a great little restaurant/ pub called Clachan. I would recommend passing the Drymmen campsite. It’s nowhere near the town as they advertise on their website. And the proprietor was not very friendly.

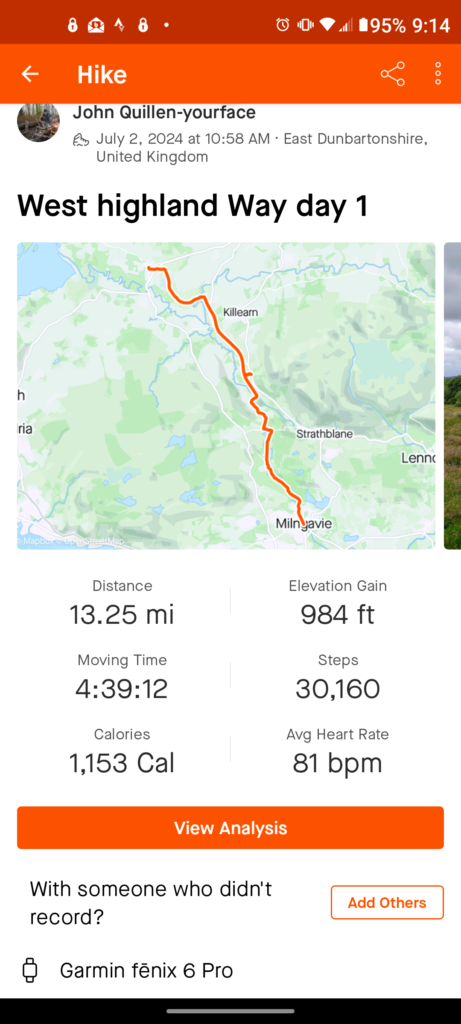

this was our initial mileage into Clachan. After a very delicious meal and a couple of beverages we pushed on to find our first wild camping spot.

it was a wonderful place in the pine trees adjacent to a pasture full of sheep which would follow us the entire trip. Okay not the same herd but sheep were everywhere.

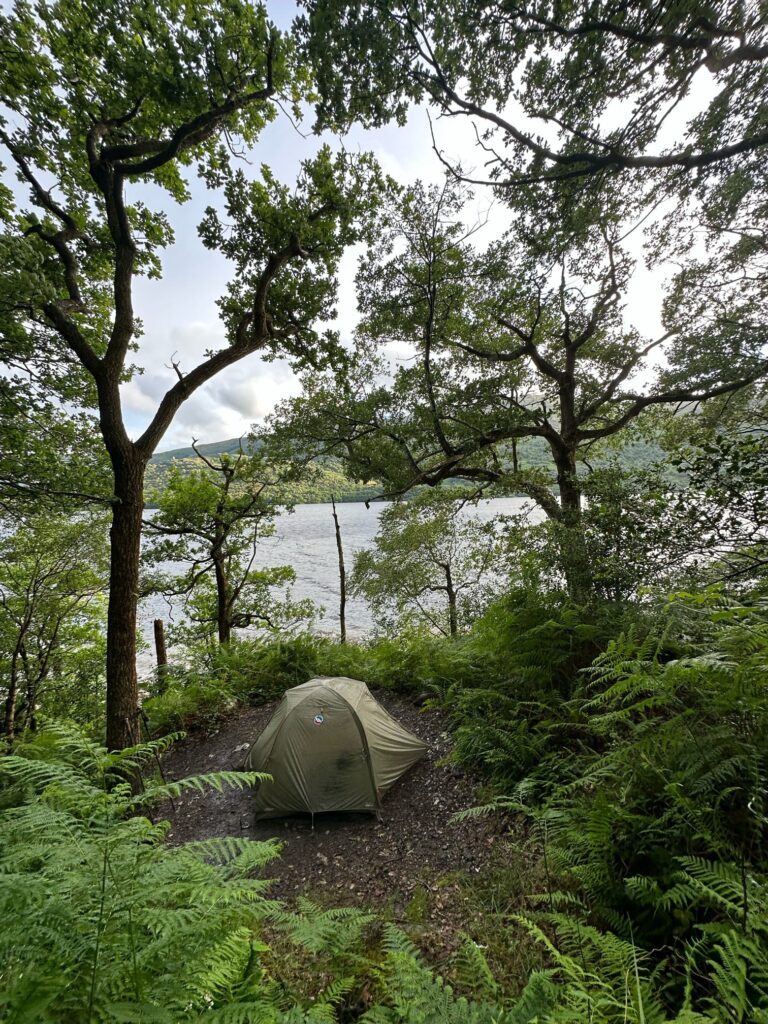

I’m posting up my mileages and GPS coordinates so folks can find their own route. Again one of the main reasons I was there was to take advantage of the Scottish wild camping rules. There’s a freedom in being able to pitch a tent wherever you like. We had a very restful night and we’re up the next morning for our days walk into the loch.

The rain began almost immediately out of camp. As a result we chose to bypass conic Hill as the views would be non-existent. This is not a deviation from the Highland Way. Just an alternate weather route. The mileage is actually longer.

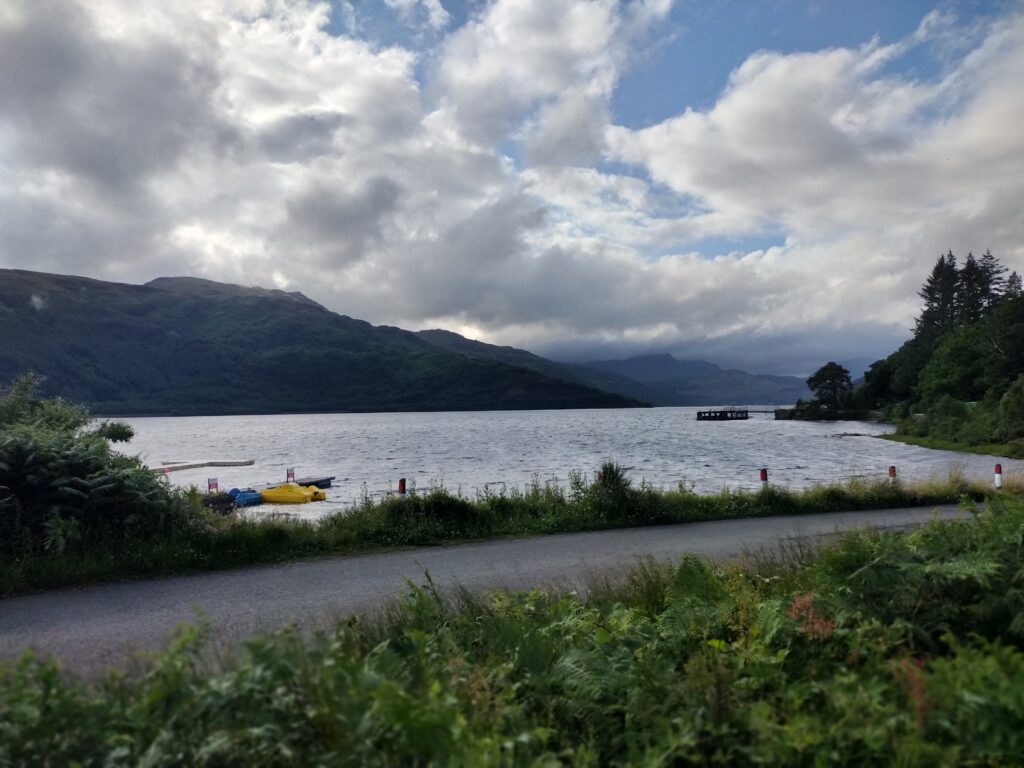

As we dropped down we got our first views of loch Lomond. But the rain persisted. We found a nice little lakeside tavern to have some lunch at Balmaha.

I’ve always wanted to spend some time in and around a Scottish loch. I’m drawn to them because I’m a water sign but also because they’re natural.. I enjoy the lakes in East Tennessee but they’re all unnatural. They are man-made. Knowing that these have been here forever as a result of the glaciers is just fascinating to me.

We got a little turned around navigationally during this rain. Eventually we were righted and started climbing some hills.

but the drizzling rain persisted.

we followed the loch for days. This day we were just resigned to having wet feet. Slosh sloshing through puddle after puddle. Climbing up and over roots.. passing the infamous Rob Roy cave. It was probably my least favorite day. We stopped at another little place for a late afternoon snack. I believe it was fish and chips. At this point we started running into fellow hikers who were having their gear shuttled in advance. I learned that most people hiking this trail didn’t really do the wild camping like we did. They would stay at hostels or nice hotels along the way. There were services that would ferry your luggage in advance.

we did right at 16.24 miles and decided to camp lakeside, once we exited the only real no camping zone along the way. The reason for this exclusion was the beauty of the loch. You can tell how people would drive up and abuse that privilege if allowed to do so. We had a beautiful spot for our second night. This was several miles outside Balmaha. I believe we hiked from there to Inversnaid and Rowardeneen.

I think we both had enough after about 12.43 miles on day 3. All the wet root walking and sloshing around took its toll.

Dry feet sounded good when we found this Backcountry shelter known as Doune bothy. This is the Scottish word for shelter apparently. And it was very nice.

We were joined that rainy night by our new friend Marius and his son and his son’s friend. These energetic young boys started a fire for us there. Toni enjoyed that.

They would shadow us for the rest of our time. Scottish hospitality is unequaled. As the rain beat down overnight we were glad to be in dry diggs. Unlike the Appalachian trail shelters this one appeared to be mouse free.

the weather promised to look a little better the following morning. So we headed towards Tyndrum.

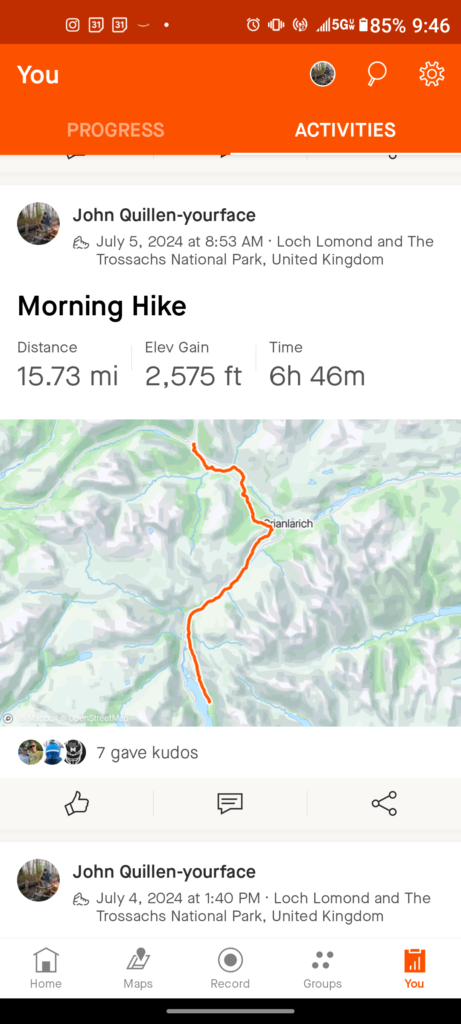

this was also a pretty wet day. By the time we came rolling into Tyndrum, we were ready to put down roots. We are done 15.73 mi this day.

we sat down at a small pub that wasn’t very hiker friendly. That night we ended up paying to camp for varying reasons. I estimated that my hiking partner was in need of a shower and some respite. The good thing about this camp spot there north of Tyndrum, is they had what’s called a drying room. There you can hang clothes and within 2 hours there would be totally dry. How they developed this technology in the middle of nowhere I have no idea but it did involve a serious dehumidifier. I don’t like paying to camp in campgrounds as you know.

But my partner was refreshed after drying her clothes and taking a shower. I did not avail myself of the shower but definitely should have. After a quick breakfast we’re back on the road, it was going to be a big day. We got turned around trying to get out of town. We regained the route and started climbing climbing climbing.

A potentially drier day was forecast, but that was not to be the case. I never removed my pack cover the entire trip nor did I hardly remove my jacket. We walked through pasteur lands and then got on to some area that was just one big muck pit. And immediately rewetted our preciously dry shoes. That was kind of aggravating.

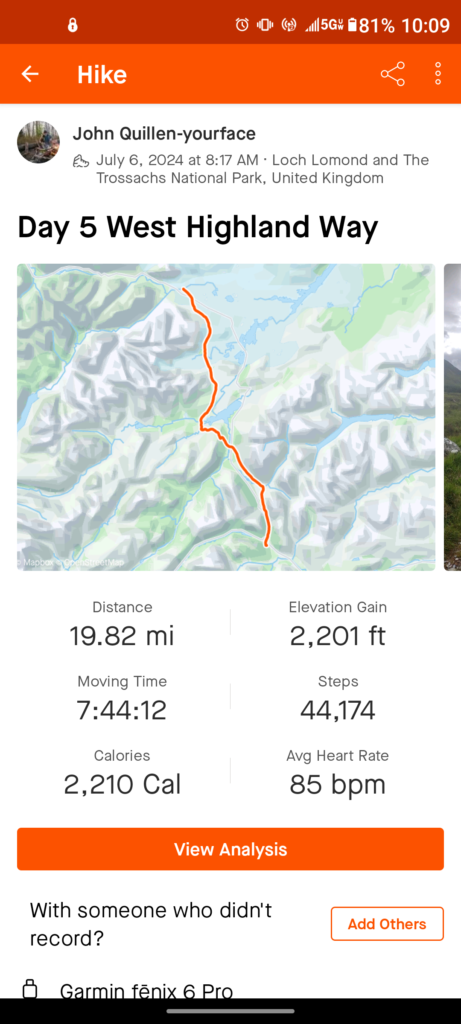

We crossed this River at the bridge of Orchy. And then started climbing. This was going to be our longest day.

I recall after crossing the bridge of Orchy, we went up a big hill. Then we were kind of alone in a pine forest. I remember a side trail heading down into Crianlarich. It was half a mile downhill so we opted not to do it. We marched on until another loch came into view. Then the weather got kind of nice for a bit. We stopped at a little place for lunch but all they had was take away pre-boxed sandwiches.. I remember being a very picturesque place. The sun was out which lifted our spirits. I purchased a chicken sandwich from the store. It may have been the worst mayonnaise chicken sandwich I’ve ever had in my life. But I scarfed it down as there was a big caloric deficiency and we had plenty more miles to go. There was a big hill coming up again. And it seemed to go on and on forever. But the landscape and scenery was dramatic.

At almost 20 miles we finally came rolling into the King’s house. This was the day that seemed like it would never end. Here in the shadow of Ben Nevis that iconic mountain. We were able to camp by the river right near the King’s house

It is a wonderful hotel, very high class. They were so kind to allow us to camp out there. It is a definite not miss area if you’re doing the West Highland Way. After a 20 mi day I was tired. Just a note if you plan on getting there and taking advantage of the pub, these pubs close early. Which means you must get your food order in as soon as you get there. By early I mean 8:00 sometimes.

A lot of climbing photography was there in the pub at the lobby of the hotel. Ben Nevis is integral to the European climbing scene.

We followed the sheep again for several miles.

This day we were to tackle the infamous devil’s staircase.

people over there make a big fuss about it but for Appalachian trail hikers it’s not that big a deal. It is a staircase up for several hundred feet.

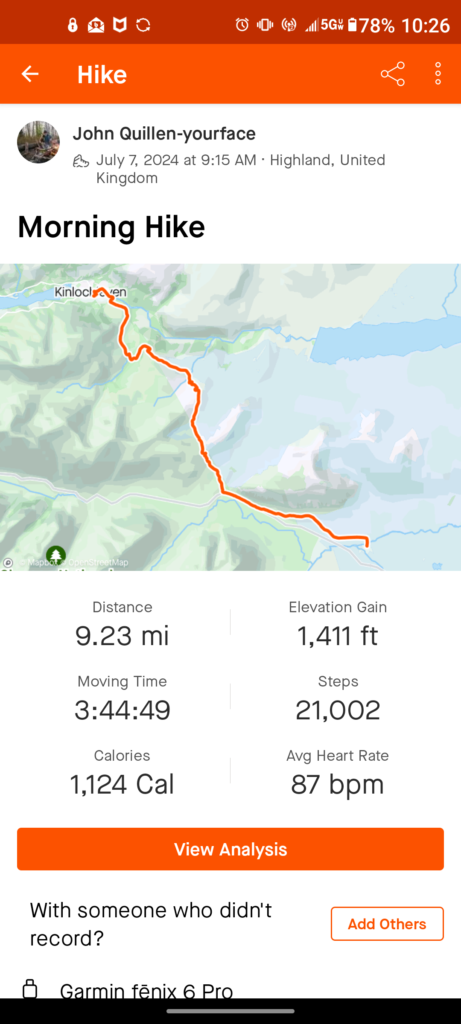

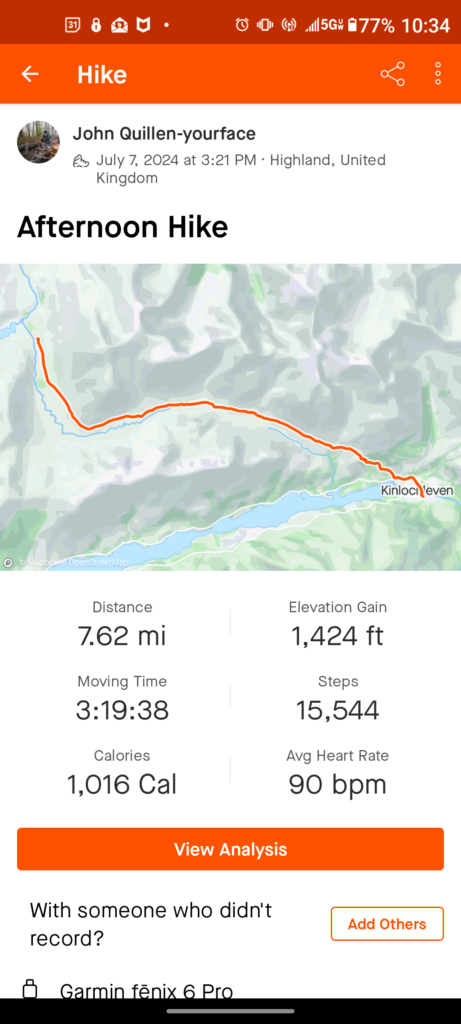

I remember after topping out having some of the best views of the trip. We were headed down into Kinlochleven. By now the sun was radiating gloriously.

behind me is what remains of the world’s indoor largest ice climbing arena. It was something to see I imagine during its day. But is now shuttered for financial reasons.

this is a view of the town after we left, having enjoyed a nice lunch in a local pub. It is a typical Scottish town. Remote and spotless. We ran across a couple of friends from Boston that were on their second day out. They had camped beside us at King’s house. I had no idea how many miles we would do this day. But the beautiful weather and trail kept luring us onward and onward.

what greeted US was another pretty good climb.

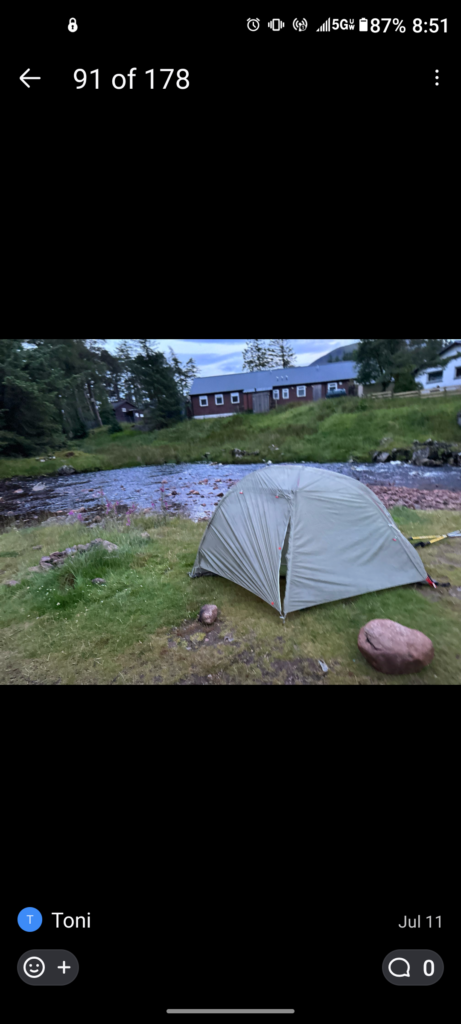

we were in some amazing geography, but there was still a lot of water on the trail. Which explains what happens next. While making one of the million crossings, Toni took a pretty good fall in the water. We walked for a bit but realized it was time to get her dry.

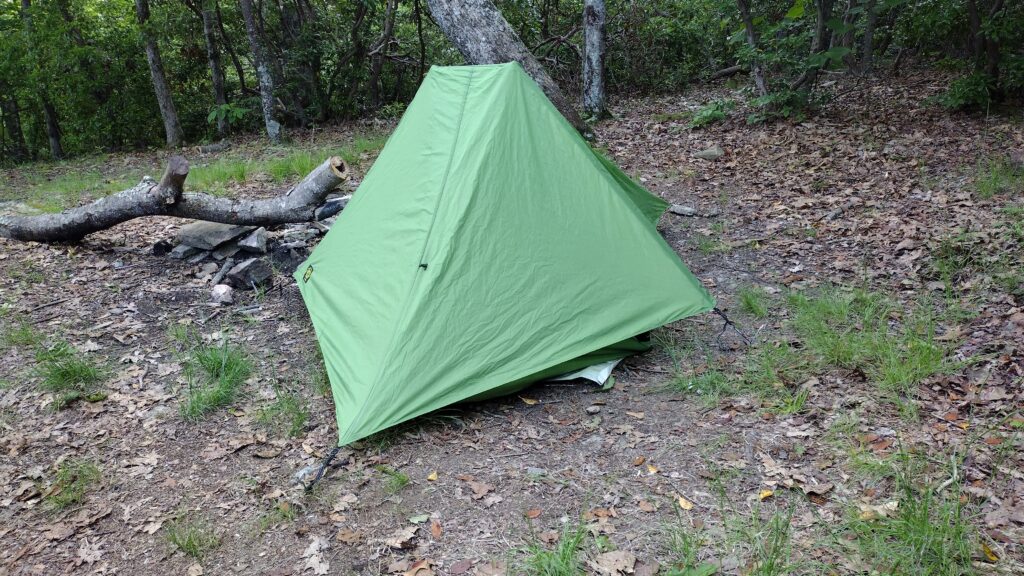

I found a nice place in the pine trees. I set up the tent and she crawled in to dry herself. She’s pretty tough in that respect. I started a small but temporary fire mainly for the smoke to keep the midges away. They are a pestilence of the first order. Imagine mosquitoes at 1/10 the size. You have to wear a headnet.

Our second leg of this day we did this many miles.

turned out being a 16.85 mi hike. Plenty for one hiking day and our blistered feet. It was a nice, peaceful and solitary camping spot.

I personally found the last few days to be some of the most picturesque of the trip. And solitary I might add. I don’t know if it’s because we were doing longer miles than most people. And I think most people were tied to itineraries due to having their luggage shuttled and staying in hotels etc. One thing I will say is that my pack was entirely too heavy. Weighing in at 40 lb I carried more gear than needed. This was because we needed to expect all kinds of weather. Strangely I used most all the gear except a couple of pieces of top layer clothing.

It’s hard to cull pictures for this experience.

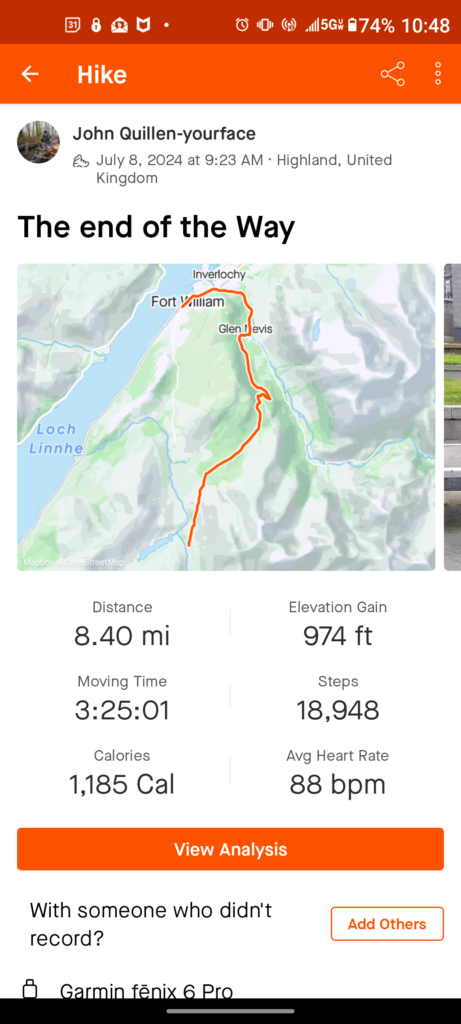

Our last day promised about 8 or 9 mi to the finish line. Much of it was downhill. We had experienced a couple of days of pretty decent weather. But that would change. One rain storm kept us on the side of the street as we entered the outskirts of Fort William. This was where we noticed a sheep had gotten its head stuck in a fence. Toni was ready to cut it out. Apparently all it took to extricate the sheep was made to jump the fence. The fear of my approach forced the sheep to pull its head out. And run free to the herd. While we sheltered under a tree from the rain, our friends Marius and the boys came marching in. We hadn’t seen them in a couple of days just before King’s house. On our big day we noticed they had pitched a Trailside camp. In a very beautiful spot I might add.

it was good to have them join us for the last leg of this journey.

Fort William is a very enchanting place. Lots of good seafood in this Oceanside town. Next time I go I plan to spend more time there. Thus our 100 mile journey was completed. 103.85 to be exact.

A truly incredible experience. This is one of those lifetime things that you cannot miss. After a night in Fort William we boarded the train down to Glasgow. It was a 4-Hour ride that retraced the majority of our journey. Of course the weather was beautiful that day. But we were able to see people hiking the trail in the distance

It was quite a sense of accomplishment to say we did that. I feel very blessed to have had this experience. Thank you Scotland and all of your hospitality.

30 miles on the AT

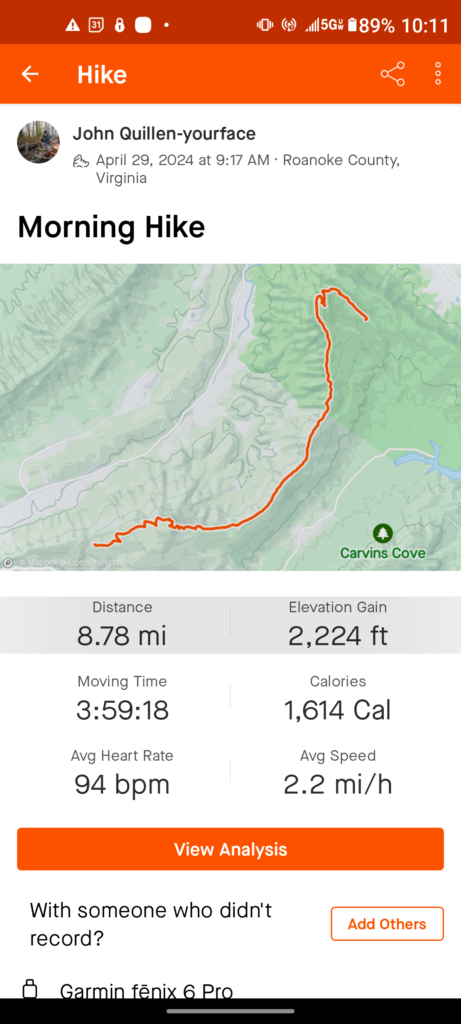

the weekend hit to finish the miles we had remaining to the James River bridge. As you will notice we finished here almost a month ago but pulled out a little early.

The first day we drove 4 and 1/2 hours up to Virginia and climbed 3,700 ft in 9 MI. When I say the weather was perfect I cannot emphasize enough how this temperature was right for the climbing. It may have been 60°.

the second day found us doing almost 12 miles. We followed the Blue ridge parkway for most of it.

we were just ahead of the bubble thank goodness.

The temperature dropped down into the 40s our first night and I’m glad I had my warmer bag. Martin and Frank did not.

the infamous guillotine

we were wary of bears in this spot. We hiked 12 miles and it was time to rest in the only place that had water. It was near here that this happened. https://thetrek.co/appalachian-trail/i-survived-a-bear-attack-on-the-appalachian-trail/

A big fire came through here a year ago and it was obvious the damage that occurred. Matts Creek.

an incredible 3-day weekend with 30 mi and lots of elevation. Great company and weather. Look at the size of this monster black snake I encountered. I would also like to make mention of the brand new helinox chair I got for my birthday from AJ. The week before we spent two nights out watching the lightning bugs in the smokies and it was glorious although we had some rain.

the Virginia triple crown

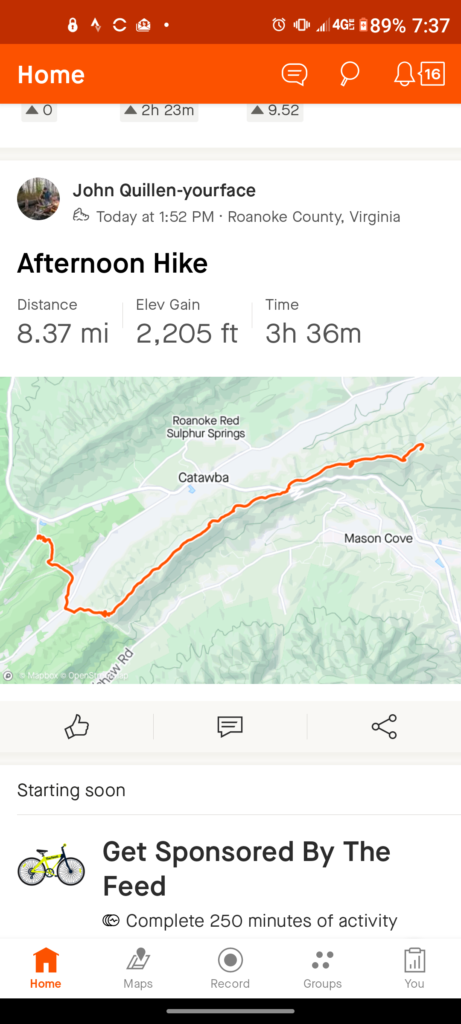

this section is considered the crown and glory of the Appalachian trail. And this is the iconic McAfee knob shot.

there was some hot hiking to get here. 88° was unexpected.

For the benefit of section hikers like ourselves there’s pretty much cell service from dragon’s tooth to troutville. Frank and I were doing this time by Martin, The Edge, Hunley.

Our miles were not that long due to the absence of water on the trail. That meant we had to carry most of what we drank for the day. So that kept us under the 12 mile per day mark.

the Appalachian trail bubble was a little bit behind us. But there were plenty of thru hikers on this section.

And an abundance of wildflowers.

They love the heat. Us, not so much.

Our second day was not much more mileage than the first.

The views on this section were incomparable.

Among our many wildlife encounters were snakes, deer, owls and ticks. Many, many, tics. We had deer in camp for our first two nights.

Do you know what kind this is?

our third day we drop down into troutville Virginia. Frank suggested that we stay at the bee cHill hostel and that was a good decision. It rained that night.

after a wonderful breakfast they prepared for us we pushed on. Coming up upon full hard knob shelter I was greeted by this site.

we had 10 miles to do this day and it was some of the best walking of the trip. We’re going to be joined by Toni, her plan was to drive from Memphis. But due to family issues at home she was forced to reconsider the decision and considering the long drive I understood. So you can imagine my surprise when she comes stumbling into camp that evening. Having driven all the way from Memphis and hiking 10 miles. She’s a beast on the trail. And I was glad to have her company.

she picked a big day of hiking.

probably the big character of our trip was a man named Homer. Homerun shuttles in this section and he picked us up at the river and took us back to our starting point. At 82 years old he is as spry as a teenager.

Homer ended up shuttling us twice but I ran into him on the trail three times. Once when we pulled into troutville he was mowing several acres of the Appalachian trail. And I do mean acres with a push mower. Then later I ran into him on the Blue ridge parkway when we popped out shuttling someone else

and of course at the end he was there to retrieve us. Such an interesting character he hiked the trail at age 62.

Frank and Martin were way ahead of us. So we enjoyed a leisurely stroll.

Our day’s hike paralleled the Blue ridge parkway for a significant amount of time.

we would have to make a dry camp, retrieving water from the bottom of the parkway and carrying at 7/10 of a mile to a knob.

our 6th days saw us doing less than 6 MI. Giving us an overall total of 55. The amount of elevation completed was11,089 feet climbing. We averaged 9.2 miles per day, and our daily elevation average was 1968.

Despite the heat I really enjoyed the section. It’s very dry though. We’re now officially one third of the way done with the Appalachian trail.

What do you think of Franks shorts?

one final note before concluding this epic journey. I did not get a single blister with all the heat and the 40 lbs we were carrying with extra water

what made the difference you may ask?

SmartWool hiking socks.

have used Darn tough before but these knock the socks off of them. @smartwool.

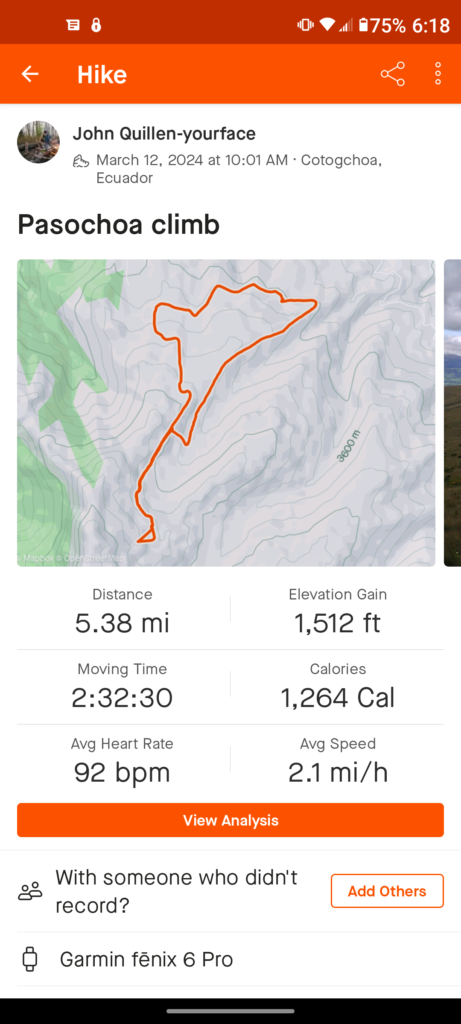

Chimborazo

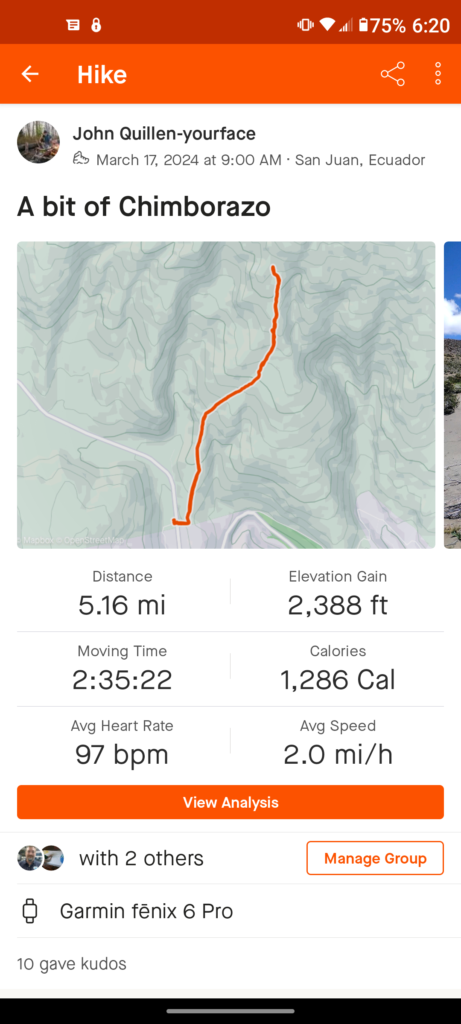

Cotocachi

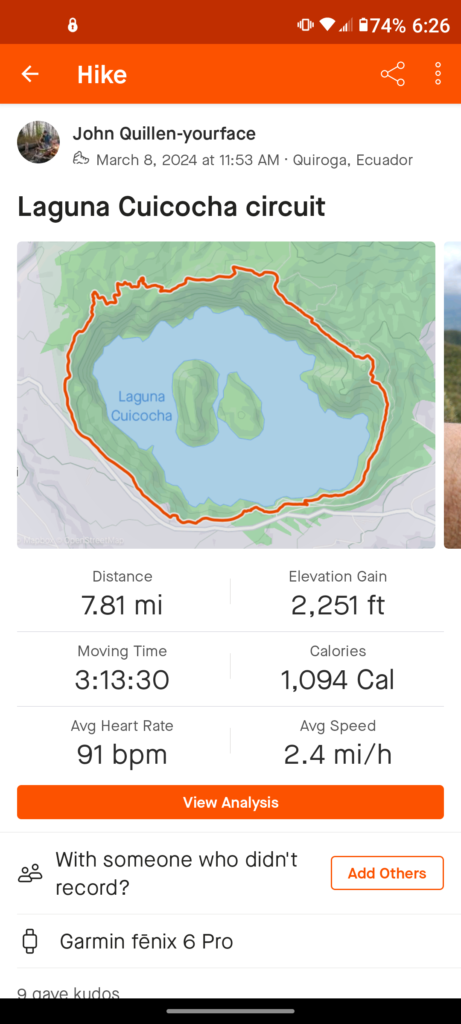

Pasochoa

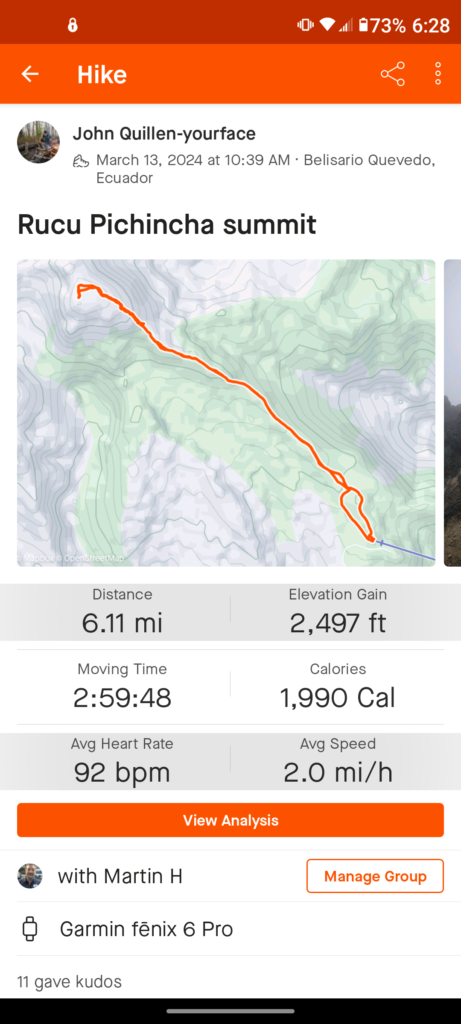

Ruccu Pichincha

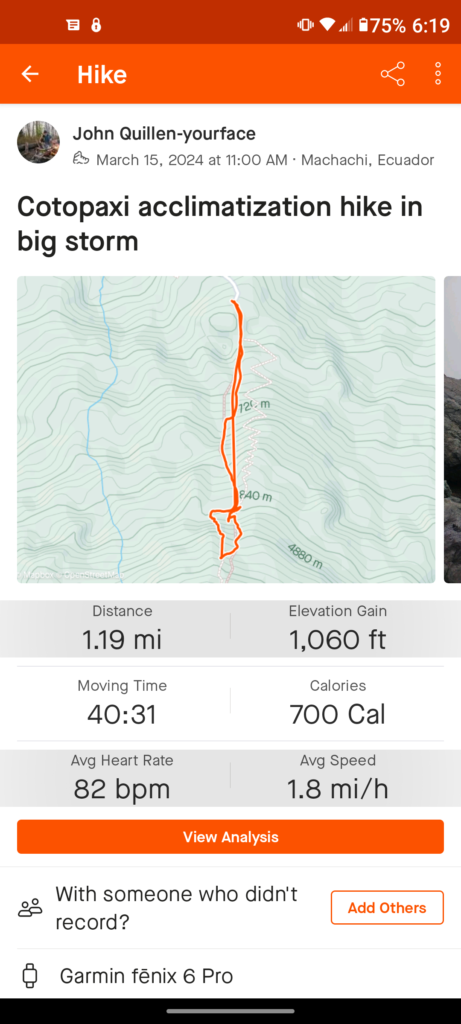

Cotopaxi (16,200 feet of it)

San Juan Achontilado.

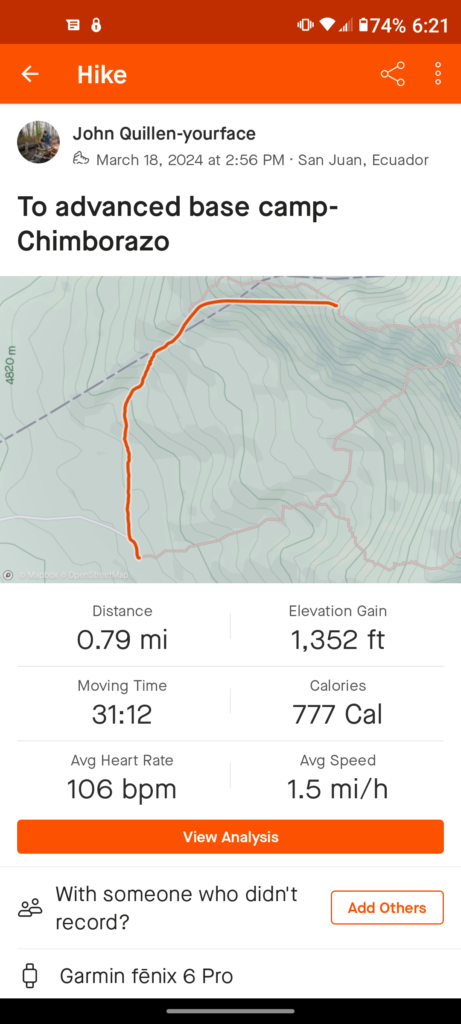

Base camp.

We set off at midnight for the summit of Chimborazo. Once again Strava was wrong here on this one. I turned around at over 19,000 ft.

Strava and garmin failed me bigly here. Along with my body. I have several theories about this. One is that I did not fully get acclimated on pasachoa due to having to descend with a client. The other is that I did not take any altitude medicine. Ordinarily I do not take altitude medicine. And I seemed to be acclimating really well. But as we slept in the high camp I woke up with a terrible headache. It was soon accompanied by nausea. This was classic a cute Mountain sickness. I still suited up and pressed for the summit, along with members of my team Richard Dan Emily and Chris. We all had private guides. My Guide from two years previous, Christian, took me on a sporting route up the via ferrata. The weather was fantastic and windless but that was soon to change. Snow moved in as we crested the peak of those metal ladders. And transitioned to the glacier. Here I caught up with the rest of the team. Richard was having trouble with his crampons. Cris was still struggling with a chest infection that dogged her throughout the journey. Emily and Dan were well ahead of us. As we slogged up in the middle of the night in the cold temperatures, wind increased. And snow peppered our faces. This was proving to be a tough endless slog. As I gained altitude my nausea took over. The dry heaving I had done in the morning after breakfast was now uncontrollable. This isn’t the first time I’ve experienced this. I’m usually able to push on through it. But here on the side of this mighty Mountain my guide gave me that look. The same one I have given other people that I’ve led up mountains. We still had a thousand vertical feet to go. And my body wasn’t having it. I descended and wished Chris and Richard the best of luck. They were in the hands of more than competent guides.

It took a couple of hours to get back to advanced base camp. There, I laid in a sleeping bag very altitude sick. I watched our team trickle back in. Dan Emily and Richard reached the first summit of Chimborazo. Although not the true summit of this peak it is over 20,000 ft. And that is quite an accomplishment. I’m proud of their determination.

we did so much more down in Ecuador though.

summit, Ruccu Pichincha

I’m so glad our entire team made it. Today we’re up for a rest day and then tomorrow we head over to the high mountains. This will include an acclimatization run on Cotopaxi or at least part of it some horseback riding at tambopaxi lodge, and then we move over to Chimborazo base camp.

Quito has been good and the weather so kind. Everyone is healthy and acclimating appropriately.

I will add some pictures from our venture.

Ouray 2024

Morristown Chamber Keynote

I was so honored to be asked to present the keynote speech to the annual Morristown Chamber meeting. John McClellan, Natasha Morrison and my brother, Todd were integral to making this happen. I was honored to share this with my family and all the Morristown people that braved the elements to support my hometown. The message was bouncing back after failure. I’ve had plenty of those, as have we all. But we push on. Where does this motivation derive? It is different for everyone, mine is but one perspective. Mountains are great levelers of men and women. As they say in N.A. and A.A., you must live “life on life’s terms”. We can’t change reality, instead, we must adapt to it. The universe is always teaching us, and that is how God makes us better in hopes we can inherit eternity. I know the good people of my hometown are ambassadors for this sentiment. I appreciate their indulgence and support. I wouldn’t have wished to grow up anywhere else. I know my home people are good stewards and reminded them of the importance of keeping public lands in public hands. This is something we at the Southern Forest Watch have fought for and continue to fight. There are battles ongoing behind the scenes. Land grabs on the Smokies borders. Myers and I are digging in and challenging the NPS on their political fealty. We did it before with a “private resort”. We now are faced with having to do it with encroachers who have not abided the park boundaries and a superintendent who turns a blind eye.

Stay tuned.

Campsite Mooch

This article could as well be about ole Ab. But it isn’t.