Cho Oyu Recap April-May 2016

It’s hard to imagine presently that one year ago I was shivering nightly in a minus 40 degree sleeping bag trying to figure out how to thaw a seemingly permanently frozen big toe. It was Andrea’s idea. At least that’s what I told people. It was his big idea to go all in on Cho. He had failed on the peak two years earlier and the itch to finish this project was gnawing. Of course, it took little for me to abandon my practice, take a leave of absence and deplete my savings for a grand adventure of this magnitude. I had a room with a view, an incredible panorama of the Himalaya jutting through my sliver of real estate in Tibet and cascading across the Nangpa la into Nepal’s portion of the greatest range on earth. That was worth 14 grand, right?

Mornings began with a breakfast bell as the sun crested Nangpa peak in the shadow of the Turquoise Goddess, Cho Oyu. Clouds wafted below us in this springtime elevation of 18,500 feet. Winter maintained her full grip on these chalky islands of rock and snow as evenings succumbed to daily storms that drove grizzled climbers deeper into down.

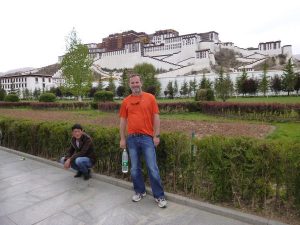

It had taken our team two weeks to arrive at what ended up being camp 3 or base camp on Cho Oyu. From our origin in Kathmandu, Nepal the journey would involve an attempted flight to Lhasa Tibet that was diverted to Chengdu, China for suspicious “weather related” reasons. That overnight stay deprived our assemblage of dinner, or any reasonable semblance thereof as we were whisked to accommodations for a brief rest prior to a second attempt on Lhasa. Four am dawned loudly as we re boarded an Air China flight and successfully touched down in the thin air of 12,000 feet on the high desert plain of the once forbidden city. The Chinese ran the Dali Llama out of his country when they invaded in 1952. Lhasa is the spiritual home of Buddhism’s spiritual leader who has remained in exile for decades. We circled the beautiful Potala Palace and breathed the dusty, thin air of higher altitude. It would require a few days of puffing before we could board buses that would ferry our group of nine mountain climbers across stark landscapes through towns called Shigatse and Tingri which required overnight stays.

Potala Palace in Lhasa.

Potala Palace in Lhasa.

My cohorts, Andrea and Freddie in Lhasa

My cohorts, Andrea and Freddie in Lhasa

Tingri was a stark place. The Clanton brothers could have faced Wyatt Earp here except that would probably require oxygen and their bullets would be better spent on feral dogs.

Tingri, with cows and canines.

Tingri, with cows and canines.

Everest from a hill overlooking Tingri

Everest from a hill overlooking Tingri

Katya (A North Col Everest client from the Ukraine, Andrea, Me and Freddie on our acclimitization hike outside Tingri)

Katya (A North Col Everest client from the Ukraine, Andrea, Me and Freddie on our acclimitization hike outside Tingri)

Canines ran this place and we were cautioned to avoid the dusty street at night. Packs of animals were known to take small children. The nights I spent there were shared with a hound from hell parked outside my window. His incessant howling was a warning. We did an acclimitization hike to gain a view of Everest shown above. Gladly we departed his city. Our last bus ride was to Chinese base camp at 14 thousand feet.

We

spent two wind whipped days here in the shadow of a military compound hiking the nearby hills for some elevation gain before embarking upon a fourteen mile walk to true advanced base camp That trip was broken by an intermediate camp wherein we were stuck for an extra day due to a snowstorm that halted our supply chain of stinking yaks and stinking yak herders. Men of dubious decree, these Tibetans burned dung in canvas tents with a smell that will never be fully dislodged from my nostrils. At the time I thought it preferable to freeze than live with such wafting filth. Soon my attitude about it would change. Intermediate camp bet BC and ABC.

Intermediate camp bet BC and ABC.

When we began our final approach to ABC, it was a seven mile day and two thousand foot gain that saw me sauntering into base camp next to last. I was ahead of Khai Ngyuen who was similarly ambling. There was little point in racing and depleting valuable energy stores this early in the ascent. I watched Freddy Johannsen and Andrea make it in record time along with several other team members as I pulled up the rear, barely ahead of the yak. The Himalaya was breath taking on multiple levels and I wished to enjoy the walk. Our expedition leader, Dani Fuller came back to check on us and was relieved to see that we were fine, just dawdling along the snow covered boulders in the last few meters before the glacier.

first view of base camp, 18 thousand feet.

first view of base camp, 18 thousand feet.

Our Summit Climb group joined a community of varying colored tents of different expeditions. There was the Jagged Globe team, a higher end British outfit that offered meals with lamb and more expensive snacks were available daily. They also had a doctor and access to weather reports that were “borrowed” by us at different times. Prior to this journey, I was convinced of the need to sign on for full services. Full service meant bottled oxygen and Sherpa support. I intended to employ oxygen for the primary reason that my previously frostbitten appendages were at risk without. It is well known that breathing “gas” improves blood flow to extremities. This weather seemed to reinforce my decision, however expensive. The addition of oxygen added $2100 dollars to my already depleted trip expenses. With Sherpa support and the derailment to Lhasa compliments of the Chinese, my investment topped 14 grand for this “grand” adventure into Tibet. Regardless, the idea of not carrying my own tent, food and stove would free me for the primary focus, climbing.

Puja ceremony

Puja ceremony

Several odd things occurred as we settled into camp and initiated our puja ceremony. A puja is a religious observation wherein objects are offered to the mountain gods and Buddhist prayers are recited over rock cairns. Climbing gear is blessed by the llama, which in our case happened to be the kitchen servant. Over the course of an hour on our second day he read from a book and threw flour into the air as our group placed crampons, ice axes, boots and all manner of gear for blessing. Soon beers were produced and the observance took on a party character.

I watched from a distance having decided well beforehand that worshiping mountain “gods” and laying equipment before them was contrary to my personal belief system. I was fairly confident that to do so would be violating one of the most important of commandments and I wished to mitigate my history by following my conscience for once. It was duly noted amongst my team members, one of whom suggested it may be “disrespectful” to the locals. I politely explained that worshiping other deities was quite “disrespectful” to my God but didn’t begrudge them for complying with the custom. I approached the Sherpa sirdar, Thile Nuru, and told him that I wished no disrespect and he seemed to understand. The ceremony ended with faces full of flour and all participants drinking beer hauled specifically for that occasion.

Immediately following the puja, David Roeske and his personal Sherpa,- — took off for the summit. If that sounds strange, it should. David was an Everest summiter from the North two years prior. At 27 years old, Roeske was a New York investment banker. His goal was to polish off Cho Oyu without oxygen and move right over to Everest and do the same. He was undoubtedly one of the fittest of our team and when he disappeared with his Sherpa on the first walk up the glacier, I had little doubts he would succeed. (David eventually summited in record time then moved over to summit the North Side of Everest without oxygen, an incredible feat by any standard) One day later, we followed in his footsteps and ascended into the clouds and snow of camp one at 21000 feet. Passing Freddie and Andrea, they recounted the horrors of the terrible scree hill. I wasn’t particularly struggling yet but this was soon to change.

Camp 1.

Camp 1.

The horrible hill is legendary on Cho Oyu. It is almost two thousand feet of movable gravel that often gives way forcing you to sacrifice your minuscule gains. Two to three steps would gain you a half foot of elevation, if you were lucky. I remember climbing for hours only to find another scree hill and no sight of camp 1. It was demoralizing. The weather turned bad halfway through the scree and our Sherpa, and young boy named Lhakpa, was already struggling with altitude. This was apparently his first expedition and he wasn’t doing well. When we arrived in camp 1, I picked an established tent and began settling in. Not many folks were there but our leader, Dani Fuller was somewhere between here and camp 2 chasing David. I had barely crawled into the tent when radio chatter indicated Dani was descending and not doing well. Soon, from the winds and overcast snow clouds, I heard Dani come “falling” into camp. He was having difficulty and needed assistance. He was also unhappy that the Sherpa had failed to come to his aid. There ensued a discussion about his radio pleading that went unanswered. We put Dani into a tent and took oxygen saturations. He had apparently scared himself with what occurred up there. He was very agitated and we had to force him into a tent and make some tea. The night was consumed with making sure he wasn’t suffering from edema, pulmonary or otherwise. It was a minimally restful evening, as are most at these heights.

The morning sun didn’t crest until about 9.30 and we began the task of melting snow and dumping loads for our descent back to ABC. Dani had survived the night at camp 1, which is more than I can say for one of our “neighbors”. As I scanned the horizon an unusual blip appeared on my radar about 50 yards from our camp. There was a mysterious pyramid of nylon that gave appearance of an old, small tent, straddling a small crevasse. This pyramid turned out to be what remained of a climber who perished her several years ago. This climber had succumbed to altitude and was left in this position, covered by the remains of a tent. It was a morbid and visceral reminder of the game we play at these heights. My water froze during the night as did I. I left the big down bag at ABC, not thinking it necessary. Instead I slept in my down suit and crawled into the 20 degree bag. That was a tactic may summit folks use on their final push. It wasn’t going to be a tactic for my summit push as I shivered uncontrollably and awakened with no drinking water. Mountaineering 101. Always sleep with your water. I put the water into a neoprene sleeve which has never failed me. It failed for certain this time.

We walked Dani back down the horrible scree hill to base camp. He had decided to avail himself of bottled oxygen given his struggling and we aided him down to the glacier. As we got within an hour of ABC, the radio announced that we would be encountering two new clients in the form of Norris Merrit and John Nigh. Norris and John had just come off an attempt to gain the North Col on Everest and were acclimatized to meet us for a full attempt on Cho Oyu. I remember meeting Norris on the glacier and watching him speak with Dani, who was breathing bottled oxygen. The scene was rather bizarre as Norris was outlining his needs with regard to a personal Sherpa and additional oxygen. Dani spoke in between breaths of his regulator.

Many days later, Dani confronted the other Lhakpa Sherpa This Lhakpa (Lhakpa is as common a Sherpa name as Jim or Joe) The inference here was that Lhakpa was more focused on his client, David, than Dani who was having problems above camp 1. The exchange between Dani and Lhakpa was quite heated and made for an uncomfortable experience in the base camp dining tent. There was a point in which I was brought into the argument, having witnessed Dani’s portion therein. I tried to remain as neutral as possible but later events would cause me to understand the nature of Dani’s anger. I did confirm that I heard Dani on the radio from camp 1. Lhakpa’s response was, “This expedition is over for me, I have nothing else to say.”

The remaining days consisted of acclimatization runs up to camp 1 and climbing between one and 2. I am not going to go into details, they are the . But here are the highlights: The weather remained cold and snowy in the afternoons. I stayed cold all night, most nights, at base camp Khai and I got lost once getting to the scree hill and that caused a bit of re navigating since we were alone. On our turns into camp 1, there was no Sherpa and no food to be found. We had to scavenge into Sherpa tents to find ramen noodles, things for which we had paid a premium price. The “full service option” added about five thousand dollars to my total once you figure in the oxygen costs. Presently, I wasn’t seeing any benefit for my expenditure.

One significant thing to note here is that our group got split into two teams. There was a first team then my team which consisted of myself, Khai, Norris, John and Chris, the Australian. Chris had trouble when he spent the first night at camp 2 and required oxygen for sleeping and assistance on descent. I passed him coming down and he was knackered. This may have been a personal altitude record for Chris and these are not unusual circumstances. The decision to split the group didn’t bother me. I always prefer the rear as the first team was comprised of rabbits I didn’t wish to chase. Being at the back always allowed me to pace myself. Like Ed Viesturs told me in Kathmandu, “Take it slow”. And I did. That proved to be my undoing on this peak. (I met Ed at a cafe in Thamel, he was there to trek in and around the Everest region with his son, Gil)

Me and the legend, Ed Viesturs in Thamel, Kathmandu.

Me and the legend, Ed Viesturs in Thamel, Kathmandu.

Fast forward to May 16th. Chris Wilcox and I were in camp 1 for the third time. Team one had successfully gained the summit of Cho Oyu and from our vantage point in perfect weather at ABC, I followed tiny dots through my binoculars as they crested the long summit plateau of Earth’s sixth highest peak. They could not have created better weather and I saw my team mates, Andrea and Freddie take their final steps miles above me as I waited anxiously in ABC for their return. It seemed as if Dani, our leader, had lost his will to climb after the altitude issues from the beginning. His lassitude was palpable and our team independently decided to move up to camp 1 and begin our assault before the weather closed. We had no Sherpa in camp until later in the morning on May 17. Chris and I decided to move up. Khai and Norris and John lounged about camp much later than my comfort level. Chris and I began the crux through the ice cliffs. The ascent here was most dramatic as there were many pitches of moderately technical ice with fixed ropes. I had never ascended ice like this on a fixed rope.

Ten hours from camp 1 found me in camp 2 with horrible wind and cold. My ascent was epic and the many pitches of near vertical ice were draining. I switched from fixed rope to fixed rope hoping to have made the right choice as many flailed in the increasing wind. I was gaining great altitude and hit a short plateau whereupon I hoped to find some tents. I did not and was instead tasked with another hour walk across a crevasse strewn plain at 23000 feet. I finally spied some nylon and hurried to disappear into one of the sanctuaries for some rest before my summit push in a few hours. It was cold, brutally cold and stark.

I yelled to see if anyone occupied this ghost town of a tent city. The omnipresent and increasing wind muffled my voice. I hear a faint response and it was from Dennis Mildenberger. I hadn’t seen Dennis for days, he apparently got sick and couldn’t join the first wave in their summit assault. Dennis had been waiting for two days up there, sipping oxygen in anticipation of our arrival and the Sherpa to escort us. Little did we know that was not to be.

I collapsed in the first available tent which happened to belong to Jagged Globe. They had abandoned it on the hill as their team forfeited their summit collectively. It was to be my home for three days in a gale unprecedented at 23,500 feet high on earth’s sixth highest peak. As I crawled into this red domicile, my body melted into a puddle atop my down bag. It was difficult to move and hydration was critical. The wind picked up as daylight ceded to Himalayan night. Soon, Chris was crawling into camp. Much later in the night, Norris was heard yelling outside of camp. He was breathing oxygen now and needed assistance. Dennis was in position to assist him into his tent. I crawled out and inflated an air mat. Norris was preparing to collapse on the snow outside of Dennis’ vestibule It would have been a near fatal mistake. We forced him to crawl inside and lay on the mat. He resisted us at first but soon acquiesced. The cold gripped my fingers and reminded of the frostbite from 2011 on Muztagh Ata. I couldn’t step out without mittens for any reason.

Now with Norris taken care of we waited on John and Khai but Norris intimated they would not be making it up. He conveyed that Khai had difficulty with the technical section and turned around. Later he muttered something about John losing a glove and being helped back by Sherpa. Either way, it was becoming apparent we would not go for the summit tonight. I layed down and began melting more water. Most folks would sleep on oxygen here but none was to be found. Sherpa were to haul it up and they were apparently in absentia. I would have to tough it out in the increasing gale that saw my tent begin to collapse in. We couldn’t hear each others voices in shouts across camp. But there was little need to convey what was happening. Hunkering down was our only option until the storm passed. Provided it did.

Day two found me holding the side of my tent from collapsing in on me. Here is a video clip.

The good weather that blessed our forbears had taken a crap on us. This was one of the bigger wind events that I have experienced in the mountains. Day two was an exercise in existence. I melted water, alone in my tent. Dennis and Norris and Chris were similarly left to their own devices. I left the tent but two times per day for obvious reasons. It was brutally cold and my fingers felt the pain whenever I removed a mitten. At some point Thile Nuru arrived and occupied another tent. It was his first time to this altitude on this expedition. How he was going to lead us up was a serious question. We were breaking down every minute at these heights but the weather was showing signs of breaking. Another night was spent freezing.The next morning, Thile Nuru came around and checked on me. Through the heavy gale, I inquired about our summit plans. Thile looked at me incredulously. “You still want to climb?” He asked. Soon he was canvassing the other domiciles asking the same questions. In two hours, he returned to inform me that we were going down. There was no oxygen for our attempts and my team mates had, according to Thile, collectively decided to descend. The “missing” Sherpa had now arrived with the sole intention of breaking down camp. They had no oxygen in their possession. My disappointment was great and all I could recall was the 14 thousand reasons to climb on. I was a bit weak, but with oxygen, about which I had so dreamed and paid, could certainly make an 8 hour climb to the summit.

As I packed up for the long slog down, the temperature bottomed out as often occurs after a big storm. I was nearer to frostbite at this point than ever on the trip and all I was doing was putting on a harness. One of the Sherpa assisted me as I knew better than to remove my fingers from the down mittens. I choked down some breakfast and coffee and helped break down the tents. Cramming everything into my pack, I began the steep rappels through the ice cliffs with the summit of Cho Oyu looming over my right shoulder. The Turquoise Goddess was not to be my prize on this expedition.

We made it to camp 1 and overnighted in the shadow of the dead climber. I was dog tired after a long descent through windswept snow and fixed ropes. I suppose it took me seven hours to make that camp. With little to no energy from the nights at high altitude, I collapsed in my tent in the now beautiful weather of Tibet. This was my luck in the mountains so often. When we had all returned the following day to base camp, it was discovered that none of us had actually indicated a desire to descend. It was a ruse. Apparently the Sherpa had told the same story to each of us. Each denied having said they indicated any desire to abandon the summit bid. It was not painfully obvious that we had been manipulated by our Sherpa who simply didn’t have the resources to get us up the mountain. Had the oxygen been present, I would have pushed on regardless. In retrospect, I wish that had been the case.

We remained in base camp for three days as no yak were available to get us back down to true base camp. Our predecessors had abandoned our camp for the relative comfort of Tingri following their successful summits. It was me, Rasmus Kragh (who did summit and remained to support us), Khai Nguyen, John, Norris and Dennis. Dani was still managing things in our base camp. When an expedition is over, you are ready to leave in many ways. Having to sit for three nights after not reaching the summit was interminable. I tried to make the best of it by hiking around and climbing small hills by my tent. I did take my first shower in over five weeks by borrowing some water from the kitchen guys and bucket bathing. It was glorious. I had to force myself to absorb the beauty of this place and not focus on the disappointment of not summiting. When we were able to depart, we made good time in 14 miles one day down to Chinese Base camp. A car was there to meet us and make the final two hour drive into Tingri where we were reunited with our rested team.

We must have looked like we felt. I was sixteen pounds lighter, sun and wind burned and haggard as the yak-men. Sad news greeted us in that I learned one of our team members lost his mother back in Canada to Alzheimer’s while we were climbing. He and I had spoken of her condition on several occasions but she had deteriorated rapidly during our time in Tibet. We retraced our steps back through the high desert plains of Tibet through Shigatse and eventually to Lhasa where we overnighted and managed to catch a direct flight back to Kathmandu. While in Kathmandu we were visited with a small earthquake that is quite common for the area.

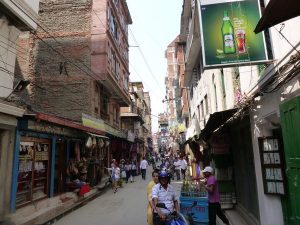

typical Kathmandu street scene of Thamel.

typical Kathmandu street scene of Thamel.

Many email exchanges were made with the leadership of Summit Climb. All of us were incredibly disappointed and angry over the turn of events at Camp 2. The resulting compromise on part of the outfitter was to offer us a 15% discount on another trip. It seemed cold comfort at the time. I’m not sure what lessons I gleaned from the Turquoise Goddess. Sometimes summits are not meant to be and I have experienced my share of peak denials throughout my climbing history. I will say that Tibet is a beautiful place and I was blessed to experience this portion of the Himalaya in all its late Spring splendor with a great group. I never fell ill, which is a first, I didn’t get injured, and returned with all my digits intact, despite having a cold toe that took a couple of weeks to rewarm. For me, that is a success and perhaps one day I will return to knock off the final portion of Cho Oyu. Presently, three of my team members on that expedition, Andrea Rigotti, Rasmus Kragh and Dennis Mildenburger are on another expedition to the summit of Everest. I wish them all Godspeed and good luck. You can follow them here at this link. http://www.arnoldcosterexpeditions.com/blog

If you enjoyed this trip tale, then you will really appreciate my first book, Tempting the Throne Room.

It was well reviewed in the climbing community and is available in many formats. I appreciate your visit to my site.

John

—-