An edited version of this story was published in Blue Ridge Outdoors Magazine, June 2019

Below is my full account of our summit push, Mt. Everest in May of 2018.

Redemption on Top of the World

7.30 p.m. 26,000 feet, South Col, Mt. Everest May 22, 2018

Ang Dawa contorts to wiggle his masked head through a shredded nylon skeleton where Neal Kushwaha and I lay in touristic repose. Drunks we were; intoxicated from purloined oxygen guzzled via discarded cylinders of undetermined age. Their contents were gladly offloaded by descending Sherpa. Our afternoon of sightseeing the moonscape of this high campsite was apparently concluded. “Go time” caught me off guard, given the hours it took me to reach the South Col, this should have been expected. Apparently, Dawa has factored my slothful pace into his summit calculus. We were abandoning 26 k Camp 4 as disparate teams brew and pack. I will be the first aspiring Everest summiter to venture onto the ominous triangular face this evening as the sun teeters off the end of the world and falls headlong into Tibet.

It takes about fifteen minutes to reach a slender slot in a vortex line of snow that culminates in a hell known as the Balcony. By culminates, I mean nine hours of suffering. But well before this, while daylight still clung to the western shoulder of Chomolungma, we climb gently into the longest night of my life.

Snow crunches beneath the weight of my boots as we approach the beginning of fixed lines. These ropes were obviously nearing the twilight of their annual use as we snatch what remains of the final two summitable days on Everest. Nine hours earlier, we took notes as our forbearers ended their negotiations with the nylon, sheathed tethers. Their gait was that of soldiers who had survived the second battle of the Somme. A few stumbled, others sat and some just slid down the endless hill. We could but imagine the expenditure of their previous 24 hours.

Presently, my effort is increasing in proportion to the slope. And daylight is but a faded memory as cold settles into my bones as we attach jumar and jockey around anchor points. Six weeks have taken us through the Khumbu Valley, up the infamous icefall, and into the dreaded Western Cwm where temperatures can soar well over 115 degrees. Yet these were just my first steps on Everest proper. Even beyond Camp 2 at the start of the Lhotse Face, we were ascending a neighbor. Lhotse is but a mere subsidiary peak. Camp 3 occupies the upper end of the Lhotse Face. It was on that face less than two days earlier a great tragedy threatened to derail our entire climb. While Neal Kushwaha, Sange Sherpa, Ang Dawa Sherpa and I rested at the base of fixed lines culminating in Camp 3, an oxygen bottle came soaring down the string of climbers above. It missed us by about fifteen feet. Our small team exited that bullseye and waited for a break in the growing mass of shapes jugging up to the Heavens.

But the next noise was not that of an oxygen tank. It was the stirring of a mountain which sloughed rock from her shoulders. People rushed passed us, casually remarking there had been some sort of accident. Descending climbers leisurely strolled back down into the cwm. We moved quickly and cautiously to the scene. In the snow at the start of fixed lines was a big red oval. One Sherpa was slouched over in what appeared to be a semi-conscious position, while another Sherpa was recoiling in great fear. Our team was struggling to foment the gravity of this situation. I walked the ambulatory Sherpa to a safe place out of the fall line of rock as Sange and Neal tended to the stricken one. The Sherpa I assisted was in his full down gear which looked to have been slashed by Jack the Ripper. Unzipping his suit, we looked for injury amidst his anguished cries and groans. To my surprise, there was no sign of bruising or blood.

Quickly, we ascertained there was little injury to treat despite his terrified gasps. He frenetically implored me to keep looking so I gingerly removed his feather- belching regalia, Aside from the obvious outward damage; no injury was to be found. With that, Ang Dawa and I turned our attention to the other, less fortunate porter that Neal and Sange had now moved to our spot atop the sunny Cwm.

Neal laid him gently down in the soft snow on a beautiful afternoon low on the ice face. I rummaged through his backpack for some type of bandage to stave the bleeding from the gaping head wound. There was so much blood. Sometimes, small cuts at the hairline can cause disproportionate trauma and I desperately hoped this was the case. It was not. We applied a temporary dressing to his head and it became apparent that his skull was cracked open like an egg. Our patient did not know his name, the name of his company or any of his team, who were nowhere to be found. Neal and Sange worked the radio, imploring our base camp manager, Kami to organize some type of evacuation for Mr. Ccherring Dorje, whose name we only later discovered. Surprisingly, there was reluctance to expend any resource for the fellow, given he had no rescue insurance. Already, we had seen half a dozen climbers pass him, unwilling to forfeit valuable summit push time. All I could think to do was have Ccherring sit upright while applying pressure from several pair of socks to his own skull. It seemed prudent to keep him upright and busy instead of laying down as he was wont to do.

A descending team from Adventure Consultants, fresh off a summit, stopped to rest and told us of a physician somewhere behind in their group. Neal and Sange feverishly worked the radio. After an hour, our basecamp manager had managed to cajole a chopper but it would require dropping Ccherring several hundred feet down, back into the lower cwm. This meant sacrificing valuable altitude and energy. Neal and Sange hesitated not. Without a thought they descended and instructed me and Dawa to stay in our spot to intercept the descending doctor. Losing hard-fought ground, my team mates didn’t give a second thought to carrying this Nepali to an evacuation spot. Before long familiar whirring portended a mechanized shadow that crested a crevassed and increasingly cloudy Western Cwm. Upon our return to Basecamp we learned that Ccherring Dorje would live another season to haul loads for climbers like me after a week in the hospital and lots of staples.

Our attention then reverted to our original and belated objective and the indignity of reclaiming part of the face. Neal, Sange, Dawa and I attached jumars and began jugging up one of earth’s highest walls into the late afternoon of May 21, 2018. We lost all daylight about two hours into a four- hour ascent on static lines that had seen the best of their days. Hard cold permeated the previously warm Lhotse face along with fears of potential frostbite. I had developed a significant case in 2011 on another peak, Muztagh Ata. This malady is well known as a high- altitude disease that can resurface with little provocation in thin air. I neglected to don the down suit since we were originally tackling the face in the heat of a cloudless morning. That was forty degrees ago and my hands were conduits for the ascending device here at 23k.

It was 10 pm when I collapsed into a tent at the upper end of Camp 3. Around us, lights flittered as stars pierced unblemished sky. Neal and I welcomed our first sips of bottled oxygen as Dawa melted snow and fluffed our pillows of steel hard ice. We retired in full cognizance this delay may have scuttled our summit attempt. In a sense, there was some relief. My summit day anxiety abated significantly as I drifted into a somnambulant rhythm of air flowing through valves and hoses into this foreign, rubber death mask. It was good to lay down. Whatever happened in the next few days was out of my hands.

(Neal and I low on the Lhotse Face prior to the accident)

A bluebird morning greeted us in our Himalayan home beneath the shadow of Nuptse and Lhotse as arcs of light refracted through some jagged sky- scape. Rest, ordinarily elusive at these heights, was easy for the both of us as we packed and snacked. Subsequent to the realization that my coffee was two thousand feet below, an omission that ordinarily would send me straight to detox, a calm overtook me this beautiful day. Dawa and Sange were goading us from cocoons of down. It was super late in the season for Everest summits. Now into May 21, the majority of the mountain’s 700 plus summiters were fleeing successfully in notorious and ballyhooed lines.

It was here that the mountain was stilled on a gorgeous spring morning as a prone object crept downward gently in my direction. A lithe climber was patiently lowering his friend through a very steep prominence of the upper face. Wrapped in a red sled with full down gear, no eyes returned my gaze from this set of helmet and goggles. He could well have been a department store mannequin; unfortunately, it was a Russian who had expired not far above. Reverently each of us clipped out of the rope while our fallen colleague was lowered as if into a grave with no bottom.

Continuing through a single rope, we gained the Yellow Band and eventually crossed up the Geneva Spur. A sense of being alone on the flanks of Everest was enveloping me as I peered skyward to nothing but a beautiful snow face that intimated the base of Lhotse’s summit. Far below me was a beast with great uniformed tail swishing left and right between anchors. There looked to be over 60 folks negotiating ropes above Camp 3. Passing the high camp of Lhotse, I was totally in sync with Everest, having encouraged our Sherpa to press on. Soon there was no one ahead or behind. Infamous landmarks beckoned me into the clouds and closer to the Col. It was getting late again and I could not possibly care any less.

In fact, I had all but abandoned the idea of summiting. Clouds were moving in and with that some wind. We were supposed to rest at the South Col and push our bid this very night. Neal and the team were two hours ahead but it still was way late. When I crossed over the Spur and rounded the final half mile into Camp 4, the sun was but a scattering of impressionist, orange slivers whose fingertips were barely clinging to this nether land on the boundary of Tibet and death. Little greeted me in this final camp but twitching headlamps, rock and cold. It was 7:50 pm, obviously too late to take off for the highest point on earth this particular evening. In darkness, I searched some 30 tents across the hostile landscape filled with flattened domes and metal cylinders. Dawa found and escorted me into a top floor room with a $50,000 view. Neal was lying on his back, sucking O’s and relaxing. “We’re too late for a push tonight” he yelled above the growing din. Our high home was little more than a makeshift teepee with buckshot holes. We had occupied an abandoned dwelling at 26,000 feet from which some Sherpa had excised their expedition logo.

“Sange says we will go tomorrow; tonight we rest here.” Neal shouts from the side of a rubber mask. This is music to my ears as the wind increases in proportion to our conversation. Secretly, I ponder the dangers of over-staying our window of time in the “Death Zone”. Himalayan winds increase as neighboring teams disappear for their night into glory. Nylon smacks me in the face but I am protected by a mask and lots of down. It is a rough summit evening and Neal conveys what I am thinking. “I’m glad we didn’t have to go out in that.”

11 p.m. 27,500 feet, May 22, 2018

My toes are numbing and the dreaded Balcony is a full two hours up. Dozens have clipped around, at my behest. Ang Dawa crouches, fully secured into static line at the upper end of the Triangular Face but well below a small prominence where we soon will exchange oxygen bottles. The night has some wind but nothing like the one before. It is steep here and I break frequently, too much I fear for Dawa’s liking, though his patience is Olympic. At times I nod off on the rope and snap to violently from dreams that are far from the top of Everest. Focus is escaping me at points. Sleep is dangerous. Several of my toes are no longer viable. Like being at the wheel on an overnight drive, I slap my legs and press onward. From this point there will be no more sleeping. I am miserable, freezing and uncertain. The steady wind beats my frozen face as stars protrude from a blanket of cloud. It is twenty below zero; no promise of sun nor summit resides in this place.

Dawa seats me on a vertiginous slope and I rely on crampons, held together with wire and chips of rock, long ago broken ascending between lower camps on the mountain. Fifteen climbers jockey for some small place to drop a knee while fumbling with canisters as mini explosions detonate randomly. Adding to the surreality of this foreboding hell are distant lightning bolts interspersed with oxygen releases that threaten to jolt each of us from our dangerous perches. These sounds have become quite familiar in this alien environment where none of us would long survive without those regulators and their fragile O-rings. I am brought to days before on the other side of this mountain where a team with Alpenglow experienced a large-scale regulator failure. My friend Dennis was in that group. My set was holding firm, my bowels, not so much. A delicate dance ensues over the precarious lip of the Balcony with me, clipped into Dawa and a rainbow zipper frozen stuck. Beyond this indignation I am reminded, “You can’t save your face and ass at the same time.”

We move upward as hints of light penetrate a Van Gough starscape. Somewhere a trace of moon competes with the promised blue warmth morning can proffer. I know my toes are frostbitten. That feeling of years ago is unmistakable. These are unretractable life decision points; niggling moments of discretion or valor. That damned nascent light magnetizes Everest so I return to a rhythmic jug and glide motion as rope disappears between my legs and across frozen toes. The sun has overtaken darkness and my face accepts warmth being the only portion slightly exposed. We are re-energized at hour 12, now 7:30 am May 23, 2018. No one is visible above or below my Sherpa brother and I here at the foot of a feature unrecognizable. This great wall of rocks appears from nowhere, formidable and austere. Portions of frayed lines dangle from varying pitons. Nothing appears new or climbable. I sit in snow as Dawa tests dangling ropes. How can it be that I was not familiar with this hindrance between the Balcony and South summit? Judging by the looks of things, neither did Dawa who was pulling on these artifacts in hopes of finding the right rope upon which to entrust our lives.

I squat to squeeze an energy gel into my mouth from the side of the oxygen mask which has now rubbed my face raw to the point of bleeding. We spend about thirty minutes here trying to decipher a climbing code with no visible clues as to where our team had ascended. As with many decisions on Everest, we pick the newest looking line and cross our mittened fingers. Astonishing is the amount of technical ability required here to gain what would later be identified as the “Castle”. I am undoubtedly fully awake and Everest holds my undivided attention. Gone are the high- altitude dreams and occasional hallucinations that have marked our time heretofore. We are front-pointing crampons I pray will hold as small chunks of Everest dislodge into my hands. This is hard work on top of hard work. Chomolungma is extracting her toll in form of sweat equity. We likely climb three to four pitches until reaching a prominent stepped slope below the South Summit. By now, teams are descending en masse from the top.

Among them is Neal and his Sherpa, Sange. It was 9 a.m. and Sange tells me it is too late. He suggests that I turn around now. I thought he was kidding. As with most things Sange, he is always smiling and joking. Dawa is ahead; by the look on his brow he has been similarly briefed. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. To go through all this and have Sange turn me around is inconceivable. Above, Dawa motions me onward and I defiantly ignore Sange’s admonitions. We soon encountered our expedition leader, Dani Fuller. He donates an extra oxygen bottle as mine is getting low. I’m not above playing the victim now. Soon we touch the flags that signify the South Summit. “You have one hour”, Dawa yells. “One hour.”

From the South Summit I can see all the features that before only resided in my dreams. We drop down a small bit and cross the infamous Cornice Traverse. Our trail is comfortably defined and sheltered. Nevertheless, a strange scene unfolds as we are stalled in an encounter with a couple presumably returning from the summit. The woman has fallen and is dangling from fixed lines in the midst of the Traverse. Her Nepali friend is yelling at her and doing nothing to assist. With little thought, Dawa reaches down and picks the woman up by her pack straps with Superman strength and places her back on the slender snow trail as we clip around them. I am fully awake, cognizant of what is going to happen very soon. Not even this freakish event derails the flow of this point in time. We could have just passed Greta Garbo and Moses but nothing was going to get between me and the summit of Everest right now. We are floating on a carpet of cream. I barely notice what remains of the Hillary Step. After the Castle, it hardly rates a mention. Dawa is blazing onward and I switch on my GoPro. The resulting footage is classic high- altitude stock. Wind is blowing our rope and Dawa is making the final steps. Everest is whipping that classic plume so familiar to us all from around the world. Our weather is perfect with adequate wind and sun.

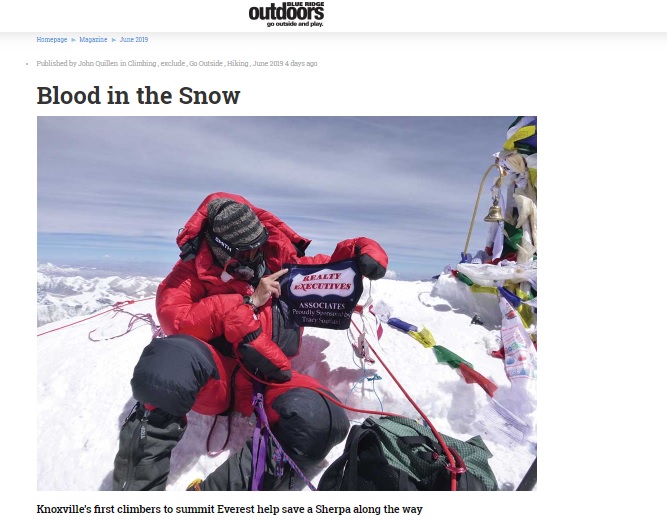

I follow Dawa for what seems like an hour before committing those last few steps myself and collapse below a small brass statue. Prayer flags snap crisply in winds that remind us we are higher than anyone else on the planet. My leg is crossed beneath me as I crane in all directions to take in this expensive earthscape. Makalu, Cho Oyu and Lhotse are clearly visible as is our path, totally empty. We are the only two humans on top of Mt. Everest and it is 10 am, May 23, 2018. There isn’t another climber anywhere on this mountain to be seen. Our panorama is uncompromised. All of which I am aware is the wind, view and tinkling of bells. This, I know, must be Heaven. There were bells in Heaven and I just got my wings.

It’s easy to lose track of time in deep hypoxia. This high beat any chemical one. There was much to photograph with sponsor flags, mementos and a special message I was tasked with placing. A young friend of mine had lost his mother many years ago. When he heard I was tackling Everest he penned a very special note to her. As I explained to my teenaged buddy, “That was probably the only reason God allowed me to get up there.” Fumbling around gloveless in -20 temps, I wasn’t sure how to best respect the “Goddess Mother of the Earth”, as Everest is known, yet still preserve the note from my young friend. Dawa shot footage of me fumbling with the note and eventually snatches it from my drunken fingers and brilliantly ties it up in a Buddhist prayer flag. My camera had frozen solid after one photograph. Forty five minutes pass like the unique morning lightning storm that welcomed us to the Balcony. Dawa is soon goading me off the Earth’s ceiling.

A long descent loomed, how long I could only presently imagine. We were alone and would be the last to come stumbling in the South Col at 7.30 pm, exactly 24 hours after departure. I fall down several times on fixed lines and make short breaks of it. For the first time I can see Dawa tiring. He had so patiently attended to me on our summit push. Now he was slowing. As the Balcony comes into view, my bowels once again remind me of the lack of atmospheric pressure here. That Triangular Face takes on a steep feeling and the South Col is but a blemish on a distant galaxy. Gone are most of the tents from a day before. Night is enfolding the Himalaya again. I remember thinking that I could just lay contentedly right here on the snow, attached to these lines. Just a few winks here and all would be fine. Then I slap myself and keep moving, wondering how many climbers had permanently succumbed to that very temptation.

Exactly one day after leaving the South Col, I collapse into what little remains of our stolen tent. Neal had apparently given me up for a Beck Weathers sort of fate. My friend is near tears at our beaten caricatures as I fall head first through the vestibule. With great care, Neal begins removing my pack and crampons. Then he asks, “Uh, shall I try to zip up your rainbow”. Apparently I had neglected to properly secure that portion of down suit following last use at the Balcony. We had a few laughs afterward when all were safe in Base Camp.

Broken nylon shreds strike at me through the night as we attempt recovery in the Death Zone. It was to be the last night of summits seen on Everest. Only six other humans depart that evening before the mountain closed her doors for good. I remove boots and examine my waxy toes. No mistake, they were frostbitten again. It was a night of fits and dreamful sleep. More than once I awaken from this position thinking the entire event had been another nocturnal imagining from Knoxville.

It is 10 am before the winds subside enough for us to finally abandon the South Col. Sange pokes his head in our tent and smiles at me above the wind as if to pretend he wasn’t serious about turning me around the day before. I accuse him of employing some form of psychology to get me going faster and he laughs saying, “It worked”. We faced a marathon day dropping into Camp 2 and a final dodge through the icefall. One of our Lhotse team, Tom Taylor, had broken his ankle in a crevasse. Our only female member had succumbed to snow blindness at the South Col and I was frostbitten. None of the route through the Khumbu Icefall is recognizable. An avalanche had swept our previous path clean and we were picking through unfamiliar penitents and towering seracs. The day is warming as thunderous mini avalanches nip at our heels. Tom is being assisted by our Sherpa through the towering, man-eating sculptures as we follow carefully behind their assemblage. Super sketch sections sprout that were heretofore absent in this “Ballroom of Death”. Our group is starting to feel like sitting ducks but none of us want to pass Tom out of respect. It is finally decided that I shall be the one to tell Tom we needed to go around, not that he would have minded. By the time I have steeled sufficient courage to make this proposition, a huge slide explodes behind us. “Go around me, John!” Tom proclaims. And with that we he was solely entrusted to the hands of our more than capable Sherpa.

Basecamp manager, Kami Sherpa greets us at the base of the Khumbu with hot drinks and crackers. We remove crampons and someone graciously liberates my backpack. I am 25 pounds lighter and it shows as we await the arrival of Tom and his entourage. Our first contact with earthlings in basecamp is a Sherpa duo. Neal inquiries about Ccherring Dorje since we have heard nothing since his evacuation. The men stand to shake our hands when they realize that we are the guys who helped one of their own. In Basecamp we examine Tom’s injury; there was little doubt his ankle was broken. It resembled a purple lab pig fully embalmed. Neither he nor I were walking anywhere far. Two days later we negotiate for a helicopter, largely subsidized by Neal that takes us as far as Namche. Everest was releasing us from her gently folding arms.

We were but five of almost 700 successful Everest climbers in 2018. Turns out we picked the right year to take our shot. Unrivaled good weather accounted for the success we enjoyed. But nothing short of Divinity allowed me the privilege of sitting atop Mt. Everest for 45 minutes alone, save for my Sherpa brother Ang Dawa. Some called it karma, I call it God’s will. We could climb that mountain fifteen more times and never experience that kind of solitude and redemption on top of the world. My toes healed but my heart was permanently swollen. This frozen giant dispatched me with blessings untold. I relish each morning with the rising sun and steam from a hot cup of gratitude. When lightning streaks a clear, black sky and storms rumble in from on high, I reach into a back pocket filled with dream dust and scatter some for the coming 24, remindful, reverent and humble.

Contact John if you need help with your Everest project or would like to schedule a speaker for your next event.