I reached the summit of 18,600 foot pico de Orizaba, Mexico’s highest point and North America’s third highest point at 8 am on Jan 4, 2017. My path to the summit went through la Malinche, detailed HERE.http://southernhighlanders.com/new/2016/12/29/summit-la-malinche

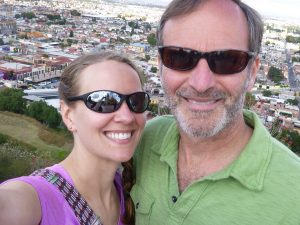

Laurel was in great form as she and I ascended the old familiar and dormant volcano that had seen my ascent two years earlier. In fact, this whole trip wa a repeat of this sojourn. http://southernhighlanders.com/mexican_volcanoes.html

Laurel was in great form as she and I ascended the old familiar and dormant volcano that had seen my ascent two years earlier. In fact, this whole trip wa a repeat of this sojourn. http://southernhighlanders.com/mexican_volcanoes.html

Think I look like a bigfoot?

Think I look like a bigfoot?

La Malinche was a lot of fun.

La Malinche was a lot of fun.  We rode a taxi from Puebla to make the summit in about 5 hours with about three for descent.

We rode a taxi from Puebla to make the summit in about 5 hours with about three for descent.  It was a taxing climb straight out of Tn and no elevation. I was proud of Laurel for pushing through the scree field to the 14 k top of this formerly smoking giant. Ironically, la Malinche was named after a native who sold out to the Spaniards and helped them conquer and colonize Mexico. We had our taxi wait for us and then return to Puebla. This is a common acclimatization trip for Orizaba aspirants. You go from 10 k to 14 k and back down. Orizaba is, from the Grand Piedra, a 4600 foot climb from 14 to 18,600. That is huge elevation for a summmit day.

It was a taxing climb straight out of Tn and no elevation. I was proud of Laurel for pushing through the scree field to the 14 k top of this formerly smoking giant. Ironically, la Malinche was named after a native who sold out to the Spaniards and helped them conquer and colonize Mexico. We had our taxi wait for us and then return to Puebla. This is a common acclimatization trip for Orizaba aspirants. You go from 10 k to 14 k and back down. Orizaba is, from the Grand Piedra, a 4600 foot climb from 14 to 18,600. That is huge elevation for a summmit day.

Returning to Puebla, we dined at the famous Mesones Sacristia de la Compagnia, where I stayed on the last trip. Their mole sauce is world famous and cheap. it was the best meal of our trip. Of course, I would proceed to catch a dose of Montezuma’s Revenge from a taco restaurant near the zocalo. That is to be expected of a John Q expedition. Speaking of the zocalo, were enjoyed the festive Christmas adornments and lively holiday atmosphere.

The cathedral is one of the oldest in Mexico and is a reverent and peaceful place. We took a few days to recover from Malinche. Our thighs and quads were spent from all the ascent and downhill pounding. I thought it somewhat strange, given the rapidity of my last ascent without any residual soreness. Attributing it to old age, I ate vitamin I(buprophen) and walked off lactic acid as we toured the following site.

Cholula

This is a huge pyramid, one of the largest in the world, supposedly. It was touted as a rival to Chichen Itza and Giza. I doubted this but we went there anyway. What we discovered was a purgatory of claustrophobic proportion. And to think we paid to walk through this underground tunnel for an eighth of a mile.

I would have paid not to have experienced that enclosure. I am not easily unnerved but to have your head scrape the top of something and shoulders rub the side of underground passageways is quite suffocating. I am more of an uphill person, not a burial mound guy. Escape was necessary.

We clamored for the heights and found the best view in Cholula. Again, a cathedral adorns the top of this former pyramid, reminiscent of the propensity to find Catholic edifices atop Christian sites in Israel and throughout the world.

We caught sight of Popocoteptl, the unclimbable, currently erupting volcano and Iztacchuatel, a smoking giant at 17k. Our ultimate goal, however, was Orizaba. it shadowed us through another sightseeing side trip to the Mexican train museum.

I recommend this trip in Puebla if you dig trains in any fashion. I inherited a love of trains from my Dad. Here, they have all manner of engines and cars that showcase the development of travel throughout Mexico.

By now we were ready to start making our way to Tlachichuca for our gateway to Orizaba via Maribel and Joaquin Concholas-Limon. Their Orizaba service is legendary and we became family the first time I lodged with them two years ago. Instead of boarding a bus and going through all the hassle therein, we decided to use something that has proven to be of great benefit. If you haven’t availed yourself of the Uber app, I strongly suggest it. We would have had to get a cab from our hotel in Puebla to Capu bus station, then board our 100 lbs of climbing/camping gear and secure two ten dollar tickets to Tlachichuca, some two and a half hours away. That is what I did last time. However, with Uber, we simply had a driver meet us at our hotel, load our gear and go straight there for about $35 US. Can you believe that? Money well spent, in my mind. I enjoy riding buses but in Mexico, you have to watch your gear. Someone could make off with it if you are not careful. This Uber opportunity alleviated that fear. And we got door to door drop off. Touring the Mexican countryside was a treat for Laurel for whom it was her first trip south of the border. We landed in Mexico City but barely caught a few hours sleep before getting on a bus to Puebla at the beginning. Had we thought of the Uber option then, things could have been different. We were super tired then and it was Christmas night.

This is a pic of the Limon compound in Tlachichuca.

We immediately went to the rooftop to catch a glimpse of our objective, dauting though it may be.

We walked around the hamlet of Tlachichuca and retired for the evening. In the morning we would make our way up to the Piedra Grande hut at 14 k via the infamous 1.5 hour 4wd trip offered by Maribel’s father, Joaquin. Joaquin is quite a character. At 72 years of age, he has retired from guiding Mexico’s highest peak. Now he is content with navigating the tricky off road ascent from Tlachichuca at 8k to the hut at 14 k. His carriages show great signs of wear as we boarded the same Jeep from two years prior through ruts and wash outs. It is quite thrilling and Laurel enjoyed the adventure, being a 4wd enthusiast herself. (she owns a vintage toyota land cruiser, circa 1985)

a view from the dashboard as we straddle the mountainside.

a view from the dashboard as we straddle the mountainside.

I found things at the refugio to be much as I left them two years ago with the exception of considerably more climbers. You may remember that I was totally alone on the mountain and in the hut, quite uncharacteristic on Orizaba for October. December and January are the peak climbing times so I was prepared for company this go around and company we did have although not too many. We said goodbye to Joaquin and set about for a mid day acclimitization run of a thousand feet or so prior to our planned alpine start of one am.

Even from here, the summit seemed miles away. Because it was. Laurel and I started up the wrong path, OK, my fault.

But she was still smiling and prepared for the longest night of her life. She just didn’t know what kind of really long night was in store. It was New Year’s day, 2017 and I guarantee Laurel will remember this evening for the rest of her life.

Jan 1, 2017 8 pm Piedra Grande Hut:, 14,000 feet, Pico de Orizaba:

I was awakened by the sound of gasping and panting. Laurel was having trouble breathing, which isn’t unusual for someone’s first time at altitude. She was having other problems in addition, though. It didn’t take long for me to diagnose her with Acute Mtn Sickness, a potentially dangerous altitude related malady for which there is but one cure, rapid descent. I had forgotten my pulse oximeter, something that is usually standard in my expedition kit. In this situation, it was probably a good thing because her saturations would have likely been in the 50s. At sea level, you are supposed to be nearly fully saturated with oxygen. My regular TN sats are 98%. In addition she was coughing and having pulse fluctuations. The problem is, we had no way to get her down until the next morning. I knew we were abandoning our summit bid and stayed up with her and tried to be reassuring. I did have emergency Dexamethasone, a high altitude rescue drug handy but didn’t want to administer it because it would be another 11 hours before a 4wd could be dispatched.

(read the sign next to poor, sick Laurel!)

(read the sign next to poor, sick Laurel!)

My only option was to sit with her, reassure her and watch her vitals. I made her pressure breathe and reduce anxiety levels and drink water. Lots and lots of water. Water thins the blood and helps carry more red blood cells to the body. Intermittently, I slept and nudged her to keep breathing deeply. During the night, our fellow hut neighbors began their preparations for summit bids. I couldn’t help but notice that the weather was ideal with no wind and a full star scape. Sometimes we would get up and go outside and enjoy a fire at 14 k. Now at midnight, all I could think about was Laurel’s safety and keeping her breathing until we could get her off this hill. It was a long night.

As our neighbors departed, Laurel dozed off and I lay in anticipation of rescue. There was a guide who returned the next morning around 10 am and helped me to radio Maribel to hasten the Jeep. Laurel went outside and began vomiting. Time was of the essence here, my finger was on the dex pill jar ready to pull.

(its pretty bad when you are laying on a rock for comfort)

(its pretty bad when you are laying on a rock for comfort)

Soon Joaquin arrived to whisk us and one successful Orizaba climber away. A Japanese lady had summited in record time from the hut and we all climbed aboard the Wagoneer and beat a retreat from Citlatepetl, aka Orizaba. Every thousand feet saw an improvement in Laurel’s condition, as I knew it would. I forced fluids down her throat and we soon were breathing the thick air of 8 thousand feet in the Concholas compound. Remarkable is the rate of recovery from altitude sickness with descent. Laurel was back to her old self by the end of the afternoon but not without a day or two of hangover type symptoms. I was able to consult with my personal, high altitude physician, Dr. Dan Walters via email who assured me that we did the right things and that Laurel would be fine. I will say that Dan has always been spot on with any medical diagnosis. He has not only prescribed my high altitude prescription medical kit, but tended to me through my frostbite situation on Muztagh Ata and aided so many through similar, trying times.

Jan 3, 2017 Tlachichuca Casa de Concholas

Laurel ate food, drank water and started being her normal self. She then insisted that I return for a summit bid. I hadn’t really though of it since I was preoccupied with her recovery but started doing the math. We had several days remaining on our itinerary and it was feasible. I still had plenty of gas in the tank. What was the weather situation? Looking good according to Mtn Weather forecasts. I started to entertain the possibility. I really wanted that summit, especially after the last two attempts. We spent the night again at Maribel’s and I mulled things over. Prior to dozing off, I decided to let Laurel’s condition be my guide. We would reassess in the morning.

Jan 4, 2017: On the rooftop again, peering up at beautiful Orizaba, aka Citlatepetel, Laurel and I enjoyed coffee and she began dancing a jig of recovery. It was at that point I knew it was safe to return to the mountain, so I ordered a Jeep and within the hour was off back up the hill. We said goodbye and Laurel resolved to mill about town and explore the hills and crannies of this small Mexican hamlet. I reboarded the Wagoneer with Joaquin and all the gear and we crawled back up the mountain that had become my nemesis. Orizaba is a beautiful strato volcano with a silhoutte rivaling some Himalayan giants. As we approached her she seemed to wink at me. I hoped this meant I had somehow curried favor in the mountain’s eyes. A few hours would tell.

Offloading my gear for the second time, I started making for another acclimatization run up the hill. This day I would scramble for two hours and gain about 1500 feet until the base of my dreaded labyrinth. It was here that I lost my way in 2014 and floundered about helplessly for hours. I was determined not to get lost in this maze and had a cache of maps from all angles prepared. As I ascended, the maps were consulted. Rock features looked all the same. I would be doing this in a couple of hours in pure darkness. My trepidation was starting to increase. Some paths would peter out and others climb into nothing. I would have to rely on other climbers as a guide. It would be a sleepless night. Returning to the hut I choked down some dinner and reminded myself why I hate dehydrated backpacker pantry meals. The next several hours would be spent lamenting an overpriced lasagna dinner as my stomach rolled and broiled. My head was formulating ways to navigate the labyrinth in the dark. Soon, the 12 midnight alarm would ring and most of the hut occupants rose to began preparations for the longest of days.

1 A.M. January 4, 2017 15000 feet pico de Orizaba

An unblemished starscape envelopes the Mexican skyline as I don double plastic mountaineering boots, multiple layers and headlamp. Metal clinks against my heavily laden backpack as a pick and adze clamor for space against two sets of metal spikes. Sooner than expected I will be attaching them to my boots as my fingers begin freezing from the efforts. I spy a line of headlamps not far above me that seem to be veering to the left and hugging a precipitous gully. From the two previous forays I knew the trail to go straight up the ridge line and followed it from memory and stones I had placed for markers just hours before. It wasn’t long before I intercepted that line of lights and found myself in their midst as foreign climbers of eastern European descent squawk at each other indiscernibly.

By three a.m. my water bottle had frozen solid much like my fingers and toes were feeling, although I knew better. Frozen digits are a specialty of mine following some poor decision making on Muztagh Ata. I knew to don down mittens and remove my watch. My hands were happier. I also passed some of the “Russians” and inched up on a guided group. We ascended this tricky section that I was able to video on the descent. In retrospect, I’m glad to have completed it in the dark.

And the steep part was hours away. I didn’t want to get too far ahead of the other climbers as I knew the crux of the labyrinth beckoned. My toes began to numb and the temps bottomed out at what had to bee single digits here at 17 thousand feet. Despite sweating from the effort of ascent heat wasn’t reaching my toes. When I spied the beginning of the true glacier, I squatted to remove crampons, boots and put on another pair of mountaineering socks. This caused me to lose the group but I was not concerned. We had finished the labyrinth and now the glacier was sole obstacle to Orizaba’s summit ridge. It was straight up a precipitous snowfield with hidden crevasses somewhere in the middle of the night. My body was trembling from cold and the time was now 5.30 am.

Praying for the sun, I started duck walking up the 35-45 degree slopes. Soon I was passing the European climbers who were laying over their ice axes in hypoxic delirium in darkness broken by star rays. The sun would soon have to rise and I mistakenly looked West for it to beckon. In mountaineering, you are at the end of your ascent when you resort to step counting. I had been here for about an hour as I spied the prominent feature known as the sarcophagus behind me. The sarcophagus is a notorious feature where an American climber fell to his death two years ago. The snow slope was now approaching 50 degrees in pitch and the seriousness of a fall became very real to me. I would not appreciate how real until the descent. 50 steps ended up being 30 steps which ended up being 20 steps then ten. I was approaching 18,000 feet now and over the wrong shoulder, traces of red broke the stars to suggest the possibility of daylight sometime. I was now past most all climbers and there were but one or two folks a few yards above. There was no definite trail to the volcano caldera. We were spilled out all over the snowfield.

Orizaba casts her long shadow over Mexico

The rising sun confers a psychological benefit but little warmth. Seeing this made me forget all about freezing.

There was little chance of not summiting. Two guys were ahead of me and approached the familiar cross and broken metal I recognized from photographs. Sulphur permeated the air as I gained the caldera ridge. Within minutes I was on top of Mexico as the rising sun hung over my left shoulder. It was 8 am and a new morning greeted us here at the top of North America. I was certain that we were, for a brief period of time, the highest people in America as no one was on Denali or Mt. Logan in the middle of winter to my knowledge.

I was very pleased and very tired. For 30 minutes I lingered, too tired to bust out the Gopro. A guide and his client did make some pics for me and I recognized one of them as John from Florida, with whom I had conversed at the hut. Orizaba was my prize, after two failed attempts. I wish that Laurel had been able to join me but after seeing the technical sections, I was glad she had been in the safety of Maribel’s home.

Here is a video I shot of the actual volcano crater, aka caldera.

It was a glorious summit day, near perfect in my estimation. However, the task of descent loomed and I wondered how to drop down that 50 degree snow slope safely. My tactic began with an ice axe and one trekking pole, side-hilling with overlapping steps. The ice axe was in my uphill hand with the trekking pole giving me something to lean on with the downhill one. It took about two hours to drop down the slope and I passed a few slit cracks in the process. Thrilled to finally finish the glacier portion, I sat down next to John from Florida who had just finished vomiting for the third time. I had felt that way myself on multiple occasions on the ascent. Now, seeing him in this state didn’t help my present circumstance. I drank some now, partially frozen water to realize it was about one half quart consumed in the last 10 hours. I ate but one energy bar and a gu gel.

It would be almost 2 pm before I got to 15000 feet and everyone had beaten me back. Many with whom I was ascending the dark, cold and precipitous snow slope had turned round, beaten by the hulking volcano. The worst moment for me was to repeat a mistake I made two years prior. On descending the icy labyrinth, there a choice to go straight or turn left. More bootpack had indicated straight but it was the wrong choice. I had, once again, dropped unnecessarily down for an eighth of a mile into the wrong gulley. The sun was now painfully strong burning my already burned forehead and neck. I was in all my layers, still in a climbing harness but stripped down to liner gloves. Re climbing that hill was the ultimate penance. I had very little uphill energy remaining. It added an hour to my return. I recognized every step from two years ago. It was an epic descent. My crampons were necessary for all but the last half mile.

When the refugio came into view, someone waved at me down the trail. It was Laurel and I was thrilled to see her back up the mountain. She was a sight for sore eyes. Not only had she conquered her altitude issue but restated a desire to return to Orizaba. Who knows, it is a fun mountain!

Happy New Year.

John

Jeff George

Damn, John. That’s a hell of an effort! I bumped into your blog via the GotSmokies website years ago and enjoy following your adventures from here in Michigan.

~Jeff

John

Thanks Jeff. I was glad to finally knock that one off. I appreciate you following.

Mackenzie

Hi John. I’m headed there next week. Any materials you can share or tips for navigating the labyrinth? Thank you!!!

-Mackenzie

John

Mackenzie,

I have a couple of maps that are helpful. This site has the most information and I printed them off and carried them on my climb.

http://www.sevenvolcanoes.com/home/orizaba

The best advice I have, though, is to follow a group if you can. I would also strongly recommend, if you plan on staying in the hut, to make the ascent through the labyrinth in the daylight prior to your climb and marking it with wands or tape. No matter how well you learn it the darkness will give you fits. I would have struggled had there not been folks in front of me.

Another notion I recommend is making a high camp at the base of the Jamapa Glacier to shorten your summit day. Then you wouldn’t have to worry about it.

Best of luck,

John